High School of the Dead and the Profitable Use of Japanese Nationalistic Imagery

Volume 18, Issue 3 (Article 9 in 2018). First published in ejcjs on 16 December 2018.

Abstract

The horror manga series High School of the Dead, which ran from 2006 to 2013, is notable for its manipulation and allusions to a variety of militarist or ultranationalist imagery. The ultimate goal of this decision remains obscure. The two artists involved, particularly the late Satō Daisuke, are known to have a personal interest in Japanese military history or war-focused media and allegedly held views that aligned with those of the Japanese ultra-Right. However, an interest in military history and contemporary weaponry does not predicate that one is sympathetic towards the further loosening of restrictions on the Japanese Self Defense Force or to arguments in favour of Imperial Japanese military actions.

Within the series itself, however, numerous narrative and character choices appear to support the ideologies of the Japanese ultra-Right. The defense alliance between the United States and Japan repeatedly fails in the wake of global catastrophe, leaving Japan open to attacks from mainland Asia. Members of the Japanese Self Defense Force and special police, unlike their overseas counterparts, are the only effective parts of the Japanese state to survive in a zombie apocalypse. Ultra-nationalists, rather than the government, create effectively defended refugee camps.

However, while the series initially appears to support ultra-nationalist ideologies, this may be a strategy utilised by the authors to distinguish their work in an oversaturated market. By artificially sparking controversy around their work, the authors ensured that they reached several target audiences, such as buki-otaku, netto-uyoku, as well as a more general audience.

Keywords: Militarist nationalism, manga, Netto-uyoku, buki-otaku, the Iraq War, New Masculinities.

Any popular cultural text springs from a specific environment. The current climate in Japan, for example, not only fosters the creation of manga and anime with nationalist themes but also allows such entertainment to thrive in a highly competitive marketplace. The manga/anime series High School of the Deadis a relatively vulgar pastiche of zombie tropes combined with hypersexual imagery that borders on ludicrous caricature of female characters. It is punctuated by extreme violence and fetishises weaponry unremittingly. But while the series regularly transgresses into bad taste and absurdity, it also touches on a vast array of nationalist themes that might go unnoticed by viewers otherwise transfixed by graphic visuals and the surreal simplicity of plot.

High School of the Dead premiered during a period when nationalist sentiment was on the rise among Japanese youth. One thread of this nationalism was militarist sentiment encapsulated from the intersection of buki-otaku1 and netto-uyoku,2 whose interest in military history and weaponry overlaps, and a simultaneous burst of anti-Korean sentiment in nationalist rhetoric encapsulated in manga, a mediumthat serves as a node for Puchi-nationalism. These social threads intersected within the series itself, which used the controversies around these groups to heighten reader interest, resulting in high sales and word-of-mouth advertising. The seventh volume of the manga peaked at the number-two position on the Oricon3 charts in May 2011 and cumulativelysold over 200,000 copies.

The artistic team behind the manga High School of the Dead were the author Satō Daisuke and artist Satō Shōji. An aficionado of military history and a sometime game designer, Daisuke4 had previously worked on other military-focused manga and alternate history fiction. His titles included a novel in which Imperial Japan goes to war against Nazi Germany5 and the Tezuka Prize6 nominated workImperial Guards. The artist Satō Shōji has a history of writing self-published hentai,7 and he tends to include semi-pornographic elements even in his more mainstream works. These traits are readily apparent in High School of the Deadin the bodies of the teenaged and adult female characters. The minutiae on the firearms, which are wielded primarily by the otherwise physically unremarkable male characters, are also lovingly detailed. While the personal tastes of both creators come through within the text, several nationalist subtexts that may hint at the creators’ political viewpoints are also apparent in the work.

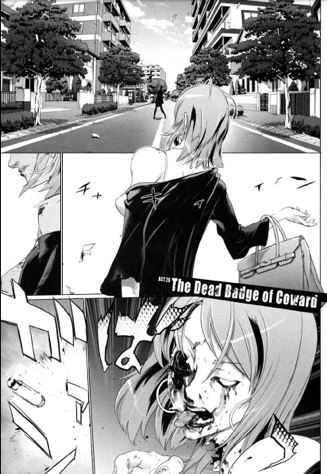

Figure 1. A Sexualised Zombie8

Fans, both domestically and internationally, quickly picked up on this subtext. The fan-run pop cultural encyclopedia TVTropesnotes in their description of the series that the creators appear to sympathise with ultranationalists and may hold anti-Korean Wave views (“Highschool”). Within Japan, the discussion of these alleged sympathies ranged from positive to extremely critical. One online amateur critic praised the series for its transgressive imagery, noting that this kept the well-worn zombie genre fresh (“Nekomegane” 2007a and b). Others decried the series as overly reliant on nationalistic imagery and violent or sexualised acts to mask a threadbare and tired narrative (“Fueisu” 2010). Still others claimed the series was an ultranationalist apologia: one commentator on Yahoo!Asks Japan answered a question about anime geared towards netto-uyokuby falsely claiming that Satō Daisuke was a criminal who drew in other ultra-rightists with an erotic grotesque zombie series that was specifically geared to the tastes of buki-otaku through the use of a moe shōjō;9 a fiery, eyeglass-wearing tsundere;10 and a number of meticulously rendered weapons (“Purofīru” 2012). This controversy worked as a form of free advertisement for the series, as new readers flocked to the series to determine for themselves the truth of these contradictory allegations.

The Aesthetic Backgrounds of High School of the Dead

The portrayal of sexuality in High School of the Deaddraws on multiple sources. Historically, such frankness is not unusual in Japanese literature. As far back as the eighth-century chronicle, Kojiki, there has been a vein of sometimes comedic eroticism within Japanese literature. That found within High School of the Dead, however, is of a decidedly different tone. Whereas historically sexuality is used for comedic or romantic effect, within High School of the Deadit tends to have an almost malicious or grotesque tone. The hyper-sexualisation of the female characters extends even to those being devoured by zombies and to the mutilated bodies of the zombies themselves.

This is a potential callback to the Erotic Grotesque Nonsense (ero guro nansenu) movement of the prewar imperial period, hereafter referred to as ero-guro. In the Imperial Period, ero-guro was criticised as a degraded, Americanised version of a purer Japanese medium (Inouye 2009: 26-28). Not only does it connect ironically to the critiques that could be leveled against High School of the Deaditself, as it derives from the foreign zombie apocalypse genre, but also further emphasises the tone set by the references to the anti-authority populist figures that are contained within the narrative, as ero-guro texts often portrayed authority figures as sexually depraved, malicious, and conniving. The extravagance, in both violence and sexuality, within this genre was a critique on the otherwise masked inconsistencies and irrationalities of contemporary society (Edwards 2013: 65). Additionally, it worked to expose members of the social margins who were otherwise invisible in media (Driscoll 2010: Amazon Kindle Location 2172). As an art movement, the genre had its heyday in the 1920s and largely evaporated during the 1930s (Silverberg 2006: Amazon Kindle Location 216), but experienced a revitalisation in the 1960s (Maruo 2015: Amazon Kindle Location 3976-3996). The aesthetic continues to be used, particularly in visual media like film and manga.

High School of the Deadalso has parallels to the works of two other manga artists known for the nationalist themes that seep into their art. The first, Kobayashi Yoshinori, is an explicitly nationalist manga writer. Like the creators of High School of the Dead, Kobayashi styles his work as subversive and countercultural to heighten his appeal to a young audience (Morris-Suzuki 2002: 151). This tactic of strategic offensiveness to draw in a youthful audience is not dissimilar from that used by the Satōs, who seem to construct much of their imagery for the sole purpose of shocking readers.

However, whether these images are meant to support the nationalist discourse within High School of the Deador subvert it through absurdist juxtaposition, is difficult to determine. It is possible that the Satōs are influenced more by Maruo Suehiro, a manga artist who is highly critical of fundamentalist or ultranationalist movements in Japan, than by Kobayashi. Maruo, like the Satōs, uses disturbing and often sexual imagery in his works, which too harken back to the ero-guro movement. But unlike Kobayashi’s, these images are meant to subvert the ostensibly fundamentalist nationalism seen in Maruo’s works. Luebke notes that in Nihonjin no Wakusei: Planet of the Jap, Maruo creates several disturbing images and connects them to what would otherwise be a clear fundamentalist nationalist narrative. By setting such parallels, Maruo undermines the fundamentalist nationalist text and provides a means of subtextually counterpointing arguments used by nationalists like Kobayashi. This technique allows Maruo to demonstrate the negative historical aspects of these forms of fundamentalist or imperial-era sympathetic nationalisms without becoming directly embroiled in an open debate (2011: 230-231).

There remains also the internationalisation of Japanese popular culture as a form of soft national power. Many manga and anime writers are aware that their material will be published abroad in some form. This has led some artists to debate the meaning of the popularity of Japanese cultural products with regard to aesthetic nationalism. Critics such as Okada Toshio have argued that Japanese popular cultural products are ‘culturally odourless’ (mukokuseki) because of their non-Japanese origins and thus could never be entirely culturally unique or play a truly dominant artistic role in Japanese society (Iwabuchi 2002: 454-456). With the awareness of a Western, usually defined as an American, gaze, other artists have begun manipulating the image of Japan within their work. Many works of popular culture now use ironic imagery—essentially satirising Orientalism through self-Orientalism—and lampoon preconceptions of Japan (Iwabuchi 2002: 459-462).

Kayama Rika coined the term Puchi-nationalism, or petit nationalism, to describe the phenomenon of nationalistic pride among contemporary youth that was primarily derived from popular culture. Kayama notes that part of the excitement surrounding football matches between teams from Japan and those of their close neighbours (for example, South Korea) is an expression of nationalistic sentiment among a population that may not consider itself overtly nationalist (Kayama 2002). Manga, due to its increasing popularity internationally, has become another focal point of Puchi-nationalism. The Japanese government exploited the growing popularity of mangaas a soft cultural tool to foster positive perceptions of Japan in multiple states, including in the People’s Republic of China (Lam 2007: 350-354). Ultranationalists in Japan, beginning with Kobayashi Yoshinori in the 1990s, have also noted that manga is a potent persuasive tool.

Negative Repercussions of the Korean Wave

In the mid-2000s, Korean media, particularly dramas such as Winter Sonata and boy pop groups, became popular in Japan. Fans mobbed the male lead of Winter Sonata, Bae Yong-joon, during his visits to Japan in the year after the series’ initial broadcast. For many, he became the face of what was known as the Korean Wave. When a zombie bearing a strong resemblance to Bae Yong-joon was killed in High School of the Dead, many interpreted the scene as an ultranationalist backlash against the Korean-wave. That this zombie was executed by a female member of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, who is shown living in a luxury apartment, is also significant. Having rid her country of an infectious, foreign interloper, the character embodied the antithesis of the horde of fans gathered outside of Bae Yong-joon’s hotel in Japan.

This anti-Korean Wave was a focal point for members of the ultraright, who relied on media and popular culture to transmit their arguments to the public. Just prior to the publication of High School of the Dead, Yamano Sharin published the controversial Hate the Korean Wave(Manga kenkanryu). The book swiftly reached the top of Amazon’s bestseller list, though its impact appears to have been minimal among the public. Bukh found that 61% of readers did not respond to the message presented by the work (Otmazgin & Suter ed. 2016: 147). However, the public may not have been the target audience of the works. Rather, it may have been aimed at the netto-uyoku, a group on average more xenophobic, and particularly anti-Korean, than the general population. Studies have shown that 70% of netto-uyokuregularly visit 2chan11 (Tsuji 2008a: 11; 2008b) these anti-Korean posts on 2chan are swiftly reposted and shared on the wider Internet without attribution (Taka 2015: 83).

The Korean Wave, also known as Hallyu, describes two separate waves of interest in South Korean popular media in Asia. The first occurred in the early 1990s, when South Korean music became suddenly popular internationally. However, in Japan, it was the second wave in the early 2000s, centred around television dramas and pop groups that caused a dramatic backlash (Chen 2016, 26). Within Japan, this second Korean Wave was driven largely by middle aged women, whose dedicated viewership launched South Korean dramas into the record books of Japanese television broadcasters (Chen 2016: 27). News media in Japan in the years immediately prior to the release of High School of the Deadaired stories that showed masses of older women waiting for hours outside of airports and hotels simply to catch a glimpse of Bae Yong-joon. One of the reasons behind the backlash may lie in a social undercurrent of misogyny, which looks upon an interest favoured largely by older, less sexually appealing women as worthy of revulsion. However, another reason is the political tensions between South Korea and Japan that linger into the present.12

There is also an apparent link between Internet usage and a rise in nationalist sentiments, largely due to the anonymity and free expression allowed in online communities (Kabashima 2016: 43). The right wing in Japan, modelling their activities on the high sales of the mangaworks of Kobayashi Yoshinori, have shifted towards the use of popular media and digital communication (Kabashima 2016: 44-45). While studies have shown that few are swayed by the messages contained within ultranationalist manga,13 the controversial and offensive aspects of these works do draw in large numbers of readers—more than previous efforts would have yielded. These works also encourage readers to explore the topic in greater detail. Readers that may have already possessed nationalistic leanings may be swayed by the pleasure of discovery and the possibility of community to become more enmeshed within the digital ultra-right, even though many will not become politically active in the real world. Through this type of outreach, a small minority can have a disproportionate impact (Kabashima 2016: 48-49). Furthermore, this series utilises its genre, the now internationally popular zombie-horror type, in a way that attracted readers who had not yet read a manga itineration of this kind.

The Manipulation of the Zombie Genre

The Satōs seemed to be fully aware that their zombie work, an American-born monster genre, would eventually be consumed abroad and adjusted their ero-guro inspired imagery inHigh School of the Deadaccordingly. Cherry blossoms bloom over a zombie apocalypse, the hyper-sexualisation of high school age female characters is combined with a moeshōjō, references to Japanese swords and pseudo-Bushido values abound, sanctuary is sought within Shintō shrines, ultranationalists meander in and out of the narrative, and one character temporarily changes from her school uniform to an elaborate kimono just to relax in a koi garden complete with a shishi-odoshi.14 This imagery adds a Japanese cultural flavour in an inherently foreign genre in a highly stereotyped manner, thereby creating a caricature of international expectations of Japanese popular culture.

The zombie archetype has a relatively short horror history when compared to the supernatural creature lexicons of both Japan and North America, the geographic origin of the monster. Originating from a syncretic blend of wildly divergent African beliefs, the progenitor zombie myth arose in Haiti and has limited resemblance to the monster seen in American, and now international, horror films. A vague outline of the zombie was imported to the United States in the early 1930s through the film White Zombie(1932, Victor Halperin). However, the zombie was only popularised just over 35 years later with the release of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead(1968). Notably, the monsters of this film were inspired by the vampires of Richard Matheson’s I am Legend(1954), but were later described as ‘zombies’ as they did not adhere to rules expected of vampires (Moreman 2010: 264-270). As recent monsters, zombies remain in flux. The mythology around them has yet to solidify, allowing authors freely to play with the creatures as well as with audience expectations.

However, there is one aspect of the zombie that remains largely consistent. Within his franchise, Romero used zombies and their relationship to the living as a representation of current social tensions (Moreman 2010: 264-267). Ultimately, scholars such as Pippen have noted that the theme that ties zombie works together is the collapse of a wealthy, developed nation through ignored social ills embodied by walking undead (2010: 40). Unlike older, more established monsters, from the European vampire to the Japanese yōkai, the zombie retains an air of menace and the flexibility to fulfill any number of symbolic roles (Stratton 2011: 268-269). Moreman and Paffenroth further this argument by positing zombie narratives as a nihilistic and cynical version of the apocalyptic, where human ingenuity and collaboration ultimately fail against the onslaught of undead (Moreman 2010: 271-271). This ties into a common thread found within postwar Japanese literature, described by Napier as the ‘apocalyptic’ (2005: 29-30).

From their importation into American cinema, zombies have had racial overtones (Brooks 2014: 461-463). Even within High School of the Dead, this theme lingers. One of the first human antagonists encountered by Takashi and Rei is a young man wearing clothing inspired by American hip-hop styles, who holds a knife against Rei’s throat and threatens to sexually assault her. This man is overpowered and injured by Takashi, who then leaves him to be devoured by a group of encroaching zombies. The last image of this character is the grimacing mouth of his zombie—mirroring his earlier, leering appearance. This scene reflects racist fears of sexual violence found in American media. Additionally, non-Japanese zombies inevitably cause the greatest amount of destruction, from the Bae Yong-joon inspired zombie holding up the evacuation of the American president from Japan to the launching of nuclear weapons from a zombie infested China.

Additionally, scholars like Stratton have argued that the rise of the zombie genre is synergistically connected to the rise of displaced persons globally. Zombies represent a life stripped of its comforts and meaning, a symbolic representation of displaced persons who find themselves in impoverished in unfamiliar surroundings (2011: 265-267). Japan has been historically hesitant to accept refugees, and to a lesser extent immigrants, in significant numbers. Notably, in 2016 Japan only accepted 28 refugees out of over 10,000 applications, shockingly low when compared to similarly sized economies in North American and Western Europe absorbing numerous refugees (Miyazaki 2017). However, the displaced within the series are often not the internationally displaced, but rather the internally displaced. Additionally, displacement also affects the ways in which gender is represented within the series.

New Masculinities

For much of Japan’s postwar period, the image of the salary-man, working long hours for a large corporation to support a middle-class nuclear family, was the defining aspect of masculinity (Hirata and Warschauer 2014: 59-60). But, with the onset of lingering economic recession, compounded by the end of the Cold War, the Kobe Earthquake, and the terror attacks perpetrated by the religious cult Aum Shinrikyo, the image of the salary-man has experienced a decline commensurate with the perceived decline of the nation. This was further compounded by political inaction at the state level, which not only failed to address economic worries but also cycled through several short-lived Cabinets (Oros 2008: 71-72). Within High School of the Dead, the male characters embody this paradigm shift. The Japanese state is incapable of maintaining order and cohesion after the rise of the living dead and promptly collapses. Within the narrative Shido, a middle school instructor, further emphasises this concept of political fragility and incompetence. As a teacher, he is tied to the Japan Teachers Union (nikkyōso), which has a reputation as a Left-leaning organisation, but he is also the son of a corrupt, local politician; he gladly fails students to intimidate their parents into dropping criminal investigations into his father.

However, the two male leads embody newer forms of masculinity that arose in response to the collapse of the previous paradigm. Hirata and Warschauer discussed three types in their work; however the most relevant to both High School of the Dead and the series’ readership are the otakuand ‘herbivore’ subcultures. These groups’ recent growth is viewed as a strategy to redefine masculinity that has become difficult to fulfill (2014: 59-60). Otakuculture was first described in the 1980s. Initially the term held negative connotations; for example the name otakuwas used to describe a series of late 19080s serial child murders in Tokyo and Saitama. However, devotion to the minutiae of media and consumption of related products has become increasingly socially acceptable (Hirata and Warschauer 2014: 67-68). This may be due to the profitability of this subgroup, whose rabid consumption is on display in the Tokyo district of Akihabara and has spawned side industries—such as pseudo-pilgrimages to locations connected to series or creators (Greene 2016).

Fukasawa Maki coined the term ‘herbivore’ in 2006, to describe men who are aggressively non-aggressive. Avoiding self-promotion, educational and professional advancement, and romantic relationships, these young men seek a life defined by passivity. Japanese commentators have targeted this group as a source of social anxiety, some claiming that over half of young men in the country have one or more herbivore trait (Hirata and Warschauer 2014: 61-63). Counter-intuitively, this group has seemingly been embraced by a significant population of young women, who view the ‘Three Highs’15 of the Bubble years as toxic (Hirata and Warschauer 2014: 64). However, these changes have not yet had an impact on Japanese social policy. Social welfare in Japan is designed to meet the needs of women and children, leaving men at high risk for extreme poverty or homelessness. The justification for this is the belief that men ought to be self-sufficient, while similar expectations are not held for their female peers (Frühstück and Walthall (ed.) 2011: 177-179).

Within High School of the Dead, the two lead male characters either embody herbivore traits, Takashi, or otaku, Kohta. Takashi is initially compared with his friend Hisashi, another student at the high school attended by most of the main cast. Hisashi is the boyfriend of Rei, and is proactive in the defense of both Rei and Takashi. Takashi is initially shown as easy-going and non-ambitious and is first seen as a teen who cuts class due to a bad mood. In contrast, Hisashi is the seeming epitome of a diligent, popular high school student, complete with a pretty girlfriend and the admiration of his peers. He and Takashi quickly realise the danger and barricade themselves and Rei on the roof of the school. But Hisashi is bitten by an infected teacher and quickly succumbs to the zombie virus. Over the objections of Rei, Takashi kills the resurrected Hisashi with a baseball bat in his first truly aggressive act of the series. Takashi then assumes a leadership role among the band of survivors from their school. However, unlike Hisashi, he did not seek this position. Nor does he attempt to maintain the strict control that Shido exerts over his group, but rather works in collaboration with the others in the group. Ultimately, Takashi’s role is to facilitate collective action between individuals with varying talents and not to serve as an authority figure or leader.

Kohta, on the other hand, is the series’ resident otaku. Overweight, easily sexually aroused, and socially awkward, Kohta is a tongue-in-cheek parody of both the target audience and the creators. This is perhaps the reason why the character that, prior to the zombie apocalypse, was both incompetent and virtually invisible, becomes vital to the group’s survival due to his knowledge derived from his obscure and unlikely hobby.16 Additionally, his physical, and initial emotional, weakness is eventually supplanted in the narrative with his ability to strategise defense and utilise weapons—skills he would not have possessed if he had selected a more socially acceptable hobby. However, this hobby is one with potentially troublesome overtones. Military otakuand war manga have perceived connection to revisionist history and the ultra-right, which has a similar interest in the creation of a strong national offensive military force. For example, Kohta names the dog adopted by the group of survivors Zero, after the fighter plane of the same name. It is this problematic affiliation, the military otaku’s love of wartime history and weaponry, which ties their interests to the political far right in the public imagination.

The difference between an individual who has an interest in the Imperial Japanese military and armament or in contemporary weaponry and the Japanese Self Defense Force due to intellectual interest and those whose similar interests are derived from their belief in the rightness of past Japanese colonial expansion or the need for a strong military unfettered from the limitations of Article Nine can be obscure. That genre works, such as High School of the Dead, are supported by a core of hardcore fans well known for their interest in aspects of the Japanese military makes the creation of such works inherently politicised (Penney 2007: 45-46). Some mangaartistsand genre writers, such as Kaizuka Hiroshi,17 Matsumoto Reiji,18 and Aramaki Yoshio19 have gone as far as to issue comments indicating that they have no connection to or sympathy with revisionists or ultra-right to quiet any preconceptions others may have due to their work in the war mangagenre and popularity among military otaku. Even when dealing with fraught topics, such as Zero pilots, these authors choose to focus more on the adventure of flight and the elaborate machinery (Penney 2007: 37-39).

Military and bukiotakuare perceived to be a largely male-dominated subculture. There is additionally overlap between military otaku and the also largely male digital far Right, the netto-uyoku. The netto-uyoku are supporters of revisionist history, believing that the current dominant historical narrative, that Japan was an aggressor that engaged in a destructive war, is false—a slander invented by foreign victors further to entrench victimhood into the national psyche (Sakamoto 2011). Netto-uyoku, however, tend to be much older than the average age of manga readers. The average age of a netto-uyoku is around 40 years old, with a university education and a high income (Tsuji 2008a: 10; Tsunehira 2016). Like herbivores and otaku, these men perform a new type of masculinity. Rather than basing their value as a man on their social position, as most possess at least two of the three above-discussed, once valued ‘highs,’ they view themselves as part of a maligned, but ultimately righteous, subculture. They ostensibly embrace their outsider status but also frequently hide their identity behind anonymous online posts.

Nor has the redefinition of masculinity been a solely civilian discussion. During the Self Defense Force’s recent deployment to Iraq, Lt. Colonel Saitō Hiroyuki noted that the organisation’s focus on humanitarian and reconstruction work was counter to the traditional image of a soldier. He stated that the concept of masculinity, which in the military had long been tied to aggressive action, needed to be redefined as someone who defends and aids the helpless, that a soldier deployed on an aid mission could be a new form of ‘militarised masculinity’ that replaces the old (Frühstück 2007: 51-52). This change is also seen in students of Japanese military academies, who in surveys value self-direction—adherence to their own values—the most while eschewing the concept of tradition due to its nationalistic overtones (Malone and Pak 2007: 176- 178). Within High School of the Dead, a female police sniper,20 Minami Rika, who guards the refugees hiding at the airport, embodies this new military. Highly trained and guided by her own mind rather than by orders, her sexualisation is almost an afterthought to the emphasis placed on her competency.

Additionally, the male members of the police force are often anonymous or appear only via reference; for example Rei’s police chief father, in the main narrative. The only regular officer to make a significant appearance is Nakaoka Asami, a traffic officer who attempts to keep a group of survivors trapped in a mall alive—a reference to George Romero’s 1978 zombie classic Dawn of the Dead. As a young woman working in one of the less prestigious branches of law enforcement, she has difficulty maintaining order within the mall until Kohta gives her a handgun. This act symbolically mirrors one of the changes in law that allowed for members of the Japanese Self Defense Forces to carry small arms for self-defense that occurred a decade prior to the series’ release (Saft and Ohara 2006: 84).Like the mall in Dawn of the Dead, zombies eventually overrun the shopping centre in High School of the Deadand Nakaoka sacrifices her own opportunity to escape to ensure the safety of others.

This emphasis on the need for the military and law enforcement to adapt to a new social order, in which they must act as humanitarian support and less as aggressive enforcers of authority resonates with the discussion of new masculinity in the Self Defense Force in the decade prior to the premiere of High School of the Dead. That this is embodied by female officers who are contrasted with the futile, but expected actions of their faceless male counterparts is likely a conscious decision on the part of the creators, particularly Satō Daisuke who was open about his interest in the Japanese military. That both Asami and Rika are also deeply enmeshed with the main group of survivors, particularly with Kohta, is significant as they are the only group of civilians who understand this new paradigm and do not react with a knee-jerk hostility against the armed branches of the state. Zombies invariably eat the many pacifists and protestors who object to this rearmament, demonstrating that postwar Japanese pacifism is ultimately self-defeating when confronted when new threats. Therefore, a greater understanding of the work’s political context may be required.

The Political Background of the Nationalisms in High School of the Dead

The Satōs did not release High School of the Dead in a vacuum; rather the series premiered in a period that possessed a number of factors that contributed to its relative success. The first is a general rise of nationalist manga and television programming as fundamentalist nationalist groups and their supporters switch the discussion from academia to popular culture, reformatting their arguments to be easily digestible in media such as manga or Websites (Morris-Suzuki 2002: 149-150). The youth audience has readily absorbed these strongly nationalist texts. Kobayashi’s Sensōron,for example, has sold over 700,000 copies, and the notorious anti-Korean Wave Kenkanryuhas sold at least 450,000 copies (Sasada 2006: 119). Manga allows for series to make a profit from a niche audiences due to its relatively low required investment, which gives this medium relative freedom in expression when compared to other visual media.

Additionally, the last twenty years have seen a slow shift in Japanese state policy towards its close neighbours, particularly South Korea. In 1993, a member of the Japanese cabinet issued an apology for the state-sanctioned rape of imprisoned women, euphemistically called “comfort women,” which satisfied few of the survivors and triggered a backlash from the ultranationalists in Japan. The rightwing protest was led partially by the History Textbook Reform Movement, whose revisionist interpretation of history erased allegations of imperial Japanese war crimes as slander. The group’s membership notably included Kobayashi Yoshinori. This group was joined by the Japan Conference, whose members can now number themselves as a majority in the current Abe administration (Kato 2014; Kazue 2016: 622-625). The anathema directed at the victims of sexual violence may be partially derived from a disregard that leads to limited interest in prosecuting sexual violence domestically and a rise in the popularity of violent pornography (Kazue 2016: 628-630). Combined with shifting notions of masculinity (Hirata & Warschauer 2014: 60-71), this creates an environment where toxic gender relations in media can flourish. The violence and sexual exploitation of the female characters within High School of the Deadis notable only for its exaggeration.

While revisionist or militarist nationalisms can be expressed explicitly in manga, television programming must be more implicit. If the imagery in the manga form of High School of the Deadcan be confrontational, its televised anime format was not allowed such freedom. Certain imagery was toned down for the television audience. For example, the character Soichiro Takagi proudly declared in the manga chapter “The Dead House Rules,” that he was the leader of an ultranationalist group (Satō 2007: 22), an affiliation excised from the High School of the Deadepisode of the same name in favour of a more oblique description. As television requires greater investment than manga, television has a tendency to reproduce banal, rather than overt, nationalism for statewide programming. The basic, least controversial concepts of what constitutes the Japanese nation and what lies outside these boundaries make up the foundational information created and transmitted by television programming (Perkins 2010: 389-392). While this means that some of the disturbing ero guro imagery used by Maruo or the Satōs or the confrontational historical nationalist ideals promoted by Kobayashi may be edited to avoid alienating potential viewers, it does not decrease the effectiveness of television as the primary medium of disseminating banal nationalism across the state (Perkins 2010: 387-388).

Figure 2. Takagi Soichiro Gives a Meiji-Era Katanato Saeko21

The Satōs, then, have an advantage of medium, as they can be quite overt in their manga and yet still have some of their imagery survive the television editing process. But they also have a favourable political environment among their targeted youth audience. Support for revisionist, anti-Korean, and militarist nationalist sentiment has comparatively risen with the youth in Japan, and even those who do not directly support nationalist movements remain more sympathetic to the arguments of historical, militarist, or conservative nationalist politicians and thinkers than previous postwar generations. There has even been a concurrent decline in support for leftist political parties, as many youths perceive these parties as overly accommodating to North Korean or Chinese demands and consider hypocritical the left’s support for domestic pacifism while relying on the American security net (Sasada 2006: 116-118).

Japanese youth tend to believe as well that the state must be responsive to the rise of Chinese economic and military might. A 2005 survey, taken shortly before the series’ publication, showed that 63.4% of Japanese youth held negative views of China; they expressed greater anti-Korean sentiment as well (Sasada 2006: 112-113). Fears of potential hostilities with either the People’s Republic of China or North Korea have further bolstered reforms made to the mandate and protocols of the Japanese Self-Defense Force (Mathur 2007: 727-730). These fears appear even to have overcome lingering taboos against Japanese military action (Ishibashi 2007: 766-768). While many leftist politicians and supporters have argued that the Japanese Self-Defense Force is unconstitutional (Sasada 2006: 110), 90.7% of Japanese youth support either the US-Japanese alliance or the formation of an independent defense. Japan’s youth are moving away from the conscious avoidance of obvious militarist nationalism historically seen in the postwar period (Sasada 2006: 112). Overt expressions of nationalism have therefore become increasingly acceptable among many consumers of manga and anime.

Three years prior to the release of High School of the Dead, Japan was one of several states that joined with the United States in the invasion of Iraq. While this participation was limited to humanitarian efforts, this represented a dramatic shift in postwar Japanese policy that had long eschewed active involvement in global conflicts. The deployment of the Self Defense Force required the alteration or passing of policies that would allow for such action, demonstrating a long and calculated interest in forwarding such changes. For example, the 2001 Anti-Terror Special Measures Law (terotaisaku tokubetsu sochihō) allowed for overseas deployment if deemed necessary by the state (Saft and Ohara 2006: 82). This was the pre-Iraq War crescendo to a decade of policy changes beginning in 1992, when the Peacekeeping Organisation Cooperation Law, that allowed for members of the Self Defense Force to carry small arms (Saft and Ohara 2006: 84), and the precursor to more recent changes, such as the 2015 lift of the ban on offensive action (heiwa anzen hōsei).

Shifting sentiments concerning the Self Defense Force in the public imagination also facilitated these changes. In the year prior to the Iraq War, polls showed that the Japanese public did not support the effort nor supported the potential participation of their state. However, in the final months before the war polls demonstrated an increasing support for both the conflict and the deployment of the Self Defense Force (Ishibashi 2007: 766-769). This shift can be partially attributed to the rhetoric found in the news media, for example the Yomiuri, that the Self Defense Force would not engage in offensive action and that the war was a necessity for global security (Lee 2016: 366-369).

Additionally, the increasing variety in media and suppliers of information allows for the potential of greater radicalism as individuals select their news sources according to their pre-established personal biases (Lee 2016: 376-378). This growing divergence also exists in entertainment media, as revisionist and ultra-nationalist groups have actively engaged in the creation of multimedia texts, from manga to video games, that align with their value system (Morris-Suzuki and Rimmer 2002: 147-151). Artists like the Satōs have thereby found multiple subcultures, from anti-Korean ultra-nationalists to buki-otaku, which can supply a steady stream of potential readers.

The shifts in defense policy in High School of the Deadis not only signified by the survival of those willing to alter their policy towards offensive violence, despite condemnation by the establishment and pacifists, but also by the need for an active and Japan-led missile defense system. Fears of missile attack began in earnest less than a decade prior to the publication of High School of the Dead, when a North Korean Taepodong missile passed over Japanese territory (Oros 2008: 170-171). However, missile defense is an elusive goal in Japan as funding for such programs experience budget cuts and any action must be undertaken with the cooperation of the United States, a complicated balancing of often mutually-exclusive interests (Oros 2008: 149-150; 170-171). This system is shown as fatally flawed in the series, as the missile defense offered by the United States fails to protect Japan from a nuclear blast, originating from mainland Asia, and the resulting EMP.

High School of the Deadis also influenced by rising globalisation. Not only has it perhaps adjusted its imagery to match an international market, but also it readily acknowledges the increasing globalisation occurring in Japan. The current generation of youth is experiencing the payoff of decades of emphasis on ‘internationalism’ (kokusaika, which is the term used for the remainder of this work), an ideology that promotes the absorption of technology and practices from the global marketplace while maintaining a distinction between imports and what is native (Iwabuchi 2002: 449). According to this ideology, strong Japanese nationalism is a threat to American and European economic and cultural hegemony, and through the perceived growth in patriotism among Japanese youth Japan is upending the historic balance of power (Iwabuchi 2002: 448-450). This concerns not only the absorption of technology but also of language, as English is considered culturally neutral and more of a tool than an artifact specific to any nation (Kawai 2009: 25-26).

This outlook is reflected in the abilities and skills of the characters within High School of the Dead. The Satōs may be combining the awareness of international readers in their work with purposefully crafted, globalised, English-speaking characters to represent kokusaikathinking. Even the titles the Satōs give to the series and chapters demonstrate this ideology: three of the titles are in English, then written phonetically in katakana, followed by a nearly identical Japanese title written in kanji. Individual chapters have titles that when rendered in English invariably include the word dead. Even the use of English within the Japanese language Internet reflects this ideology. As Japanese is largely limited to the archipelago, creators and posters largely expect that their Japanese language posts would be consumed largely by Japanese nationals (McLelland 2008: 815). In an anti-Korean 2chan thread created three years prior to the series publication, several posters who criticised their anti-Korean counterparts were assumed to be Korean and rebuttals to their posts were written in English (McLelland 2008: 822-824). Thereby, English is used as a tool to express Japanese ultra-nationalism and anti-Korean sentiments.

Within High School of the Dead,militarist nationalisms are combined with neoliberal nationalism, which developed in Japan concurrently with kokusaika. This neoliberalism holds that individuals can determine and control their fate, which should be encouraged in Japan to adapt to the globalised marketplace. This contrasts with Nihonjinron,22 which argued that one of the traits that separated Japan from other nations was the emphasis culturally placed on communalism (Kawai 2009: 19-23). These contrasting ideologies resulted in a form of neoliberalism that has holdover collectivist qualities and a positive outlook on individual ambitions and actions (Kawai 2009: 34-35). This nationalism forms the foundation of both the individual characters in High School of the Deadand their interpersonal relationships, as the characters are highly intelligent or skilled, individualised, and independent yet remain a tightly knit, empathic group.

Nationalisms as Applied to High School of the Dead

The ero guro imagery in High School of the Deadalso highlights the subtext of imperial populist nationalism. Other than the zombies, the primary antagonist of the series is Shido, a teacher and the son of a corrupt politician, who is as despotic and unethical as his father. Shido holds back one of the primary female characters, Rei, an academic grade to coerce her father into abandoning his investigation into Shido’s father’s illicit deals. Once the apocalypse occurs, Shido promptly murders a student to buy himself time to flee and uses his skills in verbal manipulation, gained from his politician father, to seduce a group of surviving students into a murderous, sex-based cult. Almost every negative attribute which imperial-era populist nationalists ascribed to politicians is found in Shido.

Only after Shido arrives at the last bastion of civilisation in the area, the base camp of the militaristic ultranationalists—the only group not to descend into chaos—does Rei expose him. The leader of the ultranationalists, Takagi, drives the cult from the area expressly because they would be a polluting influence in the ultranationalist stronghold. The readers are left with the impression that Shido and his followers are killed in the aftermath of the EMP, which disables the group’s bus. However, Shido re-appears as a potential antagonist when, in one of the final chapters of the series to be published, he appears at a school-turned-refugee camp that is presumed to be under the command of Rei’s father.

If the ultranationalists in High School of the Deadform the longest surviving state-like structure, the Leftists are invariably seen protected behind the walls of the state, deriding the actions of those defending them and demanding compassion for the zombie hordes. Leftist protestors criticise the police force who maintain the safe-zone blockade and accuse the government of committing a cover-up of their creation of the zombie plague, an accusation quickly debunked by the ultranationalist Takagi’s daughter Saya. Rather than providing the police with the space they need to act, the protestors turn into a lethal obstruction. The police commander eventually shoots the unattractive and seemingly crazed protest leader to disperse the protestors shortly before the position is overwhelmed. The last Leftist is a pro-zombie rabble-rouser within the ultra-nationalist’s compound who engages Saya in an irrational argument over the feasibility of saving the zombies. This Leftist is eventually devoured after she fails to convince an attacking zombie of her goodwill. The Left in High School of the Dead are thus shown as a ruinous, costly distraction from national defense with their insistence on paranoid contrarianism and self-defeating sympathy for a merciless enemy. This description is not far from the criticisms that are levelled by revisionists, netto-uyoku, and militarist nationalists against their ideological opponents.

In the chapter “Dead Storm Rising” a retaliatory strike with a nuclear ICBM, which may have originated from China, wipes out the electronic devices the characters depend on through an electromagnetic pulse. This nuclear strike against Japan is caused by the United States preemptively and unilaterally attacking Russia and China. The missiles reach Japan through a fatal flaw in the American security net. However, within High School of the Dead, only the Japanese Self-Defense Force is shown to act tactically and prudently, suggesting that Japan should become less reliant on American military support.

Militarism also infuses the characters themselves. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the main characters’ pet cum mascot Zeke, named explicitly after the World War Two fighter-plane by the military otakucharacter Kohta due the dog’s speed, bravery, and noise. The dog serves no other narrative purpose than to demonstrate national pride in this aircraft. The lead characters themselves are martial, as the buki otakuKohta received life-saving weapons training from a Blackwater mercenary, ultratraditional Saeko carries a Meiji General’s sword that was given to her by Takagi, Saya can strategically plan, and Rei has pike training which she applies to a bayonetted rifle. All carry arms retrieved from police or military officers. The zombies themselves may be symbolically connected to the threat posed by the rise of Korean cultural and Chinese military power needing to be defeated by young Japanese with military technology and training.

There are also gender differences in the weapons that the characters select. Saeko’s father was a master swordsman, the most recent of several generations of talented swordsmen, and he trained his daughter in the skill with the hope that either she or her husband would maintain the family’s school after his death. Also under the advisement of her father, Rei learned how to wield a pike, a weapon traditionally associated with female fighters, from her former bozozoku23 mother. Her father, a high-ranking police officer, also taught her the basics of shooting. However, Saya, Shizuka, and Alice avoid fighting and instead serve in support roles. Female characters are only empowered to defend themselves from the zombie horde if they were first trained to do so by a paternal figure. Kohta and Takashi, however, actively seek out means of defending themselves from zombies and aggressive human survivors. Takashi, and to a lesser extent Kohta, also assume leadership of the group and manipulate and fetishize the bodies of their female compatriots.

Figure 3. Takashi Using Rei as a Shooting Platform24

The main characters themselves also match a neoliberal, kokusaikaideology. They all survived initially through their own wits and effort, independent from group thinking. They are subtextually compared to their short-lived fellow-students and teachers, who were either dumbstruck by the zombies and then devoured in a mass panic or had tried to follow the dicta of the now-vanished society by blindly following circular non-leadership until they too were eradicated. This is demonstrated early in the series when Saya warns Kohta not to go to the teacher’s lounge, as they no longer can abide by previous social expectations, which is quickly emphasised when a group of students who did seek advice from the teachers are killed by the zombiefied staff. Other characters buckle psychologically under stress, and are conspicuously abandoned by the lead characters. However, the main characters are all ambitious, talented individuals who are still able to work smoothly as an essentially self-sufficient community. Notably, characters dressed as Yankī, in expensive European designer clothing, or in urban styles invariably prove incapable of surviving the zombie apocalypse due to their inability to cooperate with others or act in their own self-interest. They are shown to be consumers without culture.

Figure 4. A Man in Hip-Hop Inspired Clothing Threatening to Sexually Assault Rei25

Figure 5. Police Using Water Cannon Against Yankī26

The characters not only demonstrate a knowledge of English and critical thinking skills, but they can use foreign military technology such as an imported Humvee, imported and illegally assembled rifles, and are able to apply scientific concepts to the amateur study of both zombies and the effects of an electromagnetic pulse. Rather than allowing themselves to be absorbed into larger social groups, which the characters had the chance to do on at least three occasions, the group elects to remain in a smaller, more adaptable group to follow their own goals. This matches the expectations of both neo-liberal and kokusaikanationalisms.

The Satōs’ skillful and layered use of nationalisms is amazingly complex, despite their ultimate goals and opinions remaining opaque. Are they attempting to mimic Kobayashi, being shocking to draw in a young audience for their fundamentalist nationalism? Or are they following a similar logic to Maruo, using disturbing ero guro imagery to undermine the nationalist messages? They also may have created a work that is confrontational simply to attract media attention. However, the nationalist subtexts remain apparent to the audience as militarist nationalisms and related ideologies provide a foundation for both the imagery and narrative content. Considering the number and depth of nationalisms involved in the narrative devices and imagery in High School of the Dead, and the text’s relative popularity, its relevance for understanding of how the rise in nationalist expression has affected the popular cultural environment of youth cannot be understated.

References

Brooks, Kinitra D. (2014). The Importance of Neglected Intersections: Race and Gender in Contemporary Zombie Texts and Theories. African American Review, 47.4, 461-475.

Bukh, Alexander (2012). Reception of Revisionist Historical Mangain Japan: A Case Study of University Students. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 13:4, 623-638.

Castro-Vazquez, Genaro (2012). Language, Education and Citizenship in Japan. New York: Routledge.

Chen, Steven (2016). Cultural technology: A framework for marketing cultural exports—analysis of Hallyu (the Korean wave). International Marketing Review, 33:1, 25-50.

Delury, John (2015). The Kishi Effect: A Political Genealogy of Japan-ROK Relations. Asian Perspective, 39, 441-460.

Driscoll, Mark William (2010). Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895-1945. Durham: Duke University Press.

Edwards, Justin D., and Rune Graulund (2013). Grotesque. New York: Routledge.

Feisu. “ Feisu no chōbun okiba.” Gakuen mokushiroku haisukūru Obu za deddo. N. P., 06 Oct. 2010. U~ebu. 30 May 2017. http://icekbgface.blogspot.com/2010/10/blog-post.html.

Frühstück, Sabine (ed.) (2007). Uneasy Warriors. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Frühstück, Sabine and Anne Walthall (ed.) (2011). Recreating Japanese Men. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Greene, Barbara (2016). FuruSatōand Emotional Pilgrimage: Ge Ge Ge no Kitaroand Sakaiminato. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 43:2, 333-356.

“Highschool of the Dead / Characters.” TV Tropes. TVTropes.org, n.d. Web. 30 May 2017. http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Characters/HighSchoolOfTheDead.

Hirata, Keiko, and Mark Warschauer. Japan: The Paradox of Harmony. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

Inouye, Rei Okamoto (2009). Theorising Manga: Nationalism and Discourse on the Role of Wartime Manga. Mechademia, 4, 20-37.

Ishibashi, Natsuyo (2007). The Dispatch of Japan’s Self Defense Forces to Iraq: Public Opinion, Elections, and Foreign Policy. Asian Survey, 47:5, 766-789.

Iwabuchi, Koichi (2002). “Soft” Nationalism and Narcissism: Japanese Popular Culture Goes Global. Asian Studies Review. 26:4, 447-469.

Japanese Comic Ranking (2011, May 18), May 9-15. Retrieved from: http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2011-05-18/Japanese-comic-rating-May-9-15

Japanese Comic Ranking (2011, May 25), May 16-22. Retrieved from: http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2011-05-25/Japanese-comic-rating-May-16-22

Kabashima, Eiichiro (2016). Intānetto to `kageki-ka' ni tsuite no kōsatsu intānetto wa dono yō ni shikō to giron, shakai o kaeru no ka. Aoyama chikyū shakai kyōsei ronshū sōkan-gō, 43-62.

Kato, Norihiro. “Japan's Rising Nationalism.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 12 Sept. 2014.

Kawai, Yuko (2009). Neoliberalism, Nationalism, and Intercultural Communication: A Critical Analysis of a Japan’s Neoliberal Nationalism Discourse under Globalisation. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication. 2:1, 16-43.

Kayama, Rika. Petite nationalism syoukougun—Wakamono tachi no nippon syugi. Chuoukouronshinsha: Tokyo, 2002.

Kazue, Muta (2016). The ‘Comfort Women’ Issue and the Embedded Culture of Sexual Violence in Japan. Current Sociology Monograph. 64:4, 620-636.

Lam, P.E. (2007). Japan’s Quest for “Soft Power:” Attraction and Limitation. East Asia, 24, 349-363.

Lee, Jooyoun (2016). Narrating War: Newspaper Editorials on Japan’s Defense and Security Policy between Militarism and Peace. The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 28:3, 265-382.

Low, Harry. “How Japan Has Almost Eradicated Gun Crime.” BBC News, BBC, 6 Jan. 2017.

Luebke, Peter C, & DiNitto, Rachel (2011). Maruo Suehiro’s ‘Planet of the Jap:’ Revanchist Fantasy or War Critique? Japanese Studies. 31:2, 229-247.

Malone, Eloise Forgette and Chie Matsuzawa Paik (2007). Value Priorities of Japanese and American Service Academy Students. Armed Forces & Society, 33:2, 169-185.

Mathur, Arpita (2007). Japan’s Self Defense Forces: Towards a Normal Military. Strategic Analysis, 31:5, 725-755.

Maruo, Suehiro et al (2015). Eureka 2015 nen 8 gatsugou = Edogawa Ranpo. Tokyo: Seidosha.

McLelland, Mark (2008). ‘Race’ on the Japanese internet: discussing Korea and Koreans on ‘2-channeru’. new media & society, 10:6, 811-829.

Miyazaki, Ami, and Minami Funakoshi. “Japan Took in Just 28 Refugees in 2016, despite Record Applications.” Reuters, 9 Feb. 2017

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa, & Rimmer, Peter (2002). Virtual Memories: Japanese History Debates in Manga and Cyberspace. Asian Studies Review. 26:2, 147-164.

Napier, Susan J (2005). Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Nekomegane Second. “ Gakuen mokushiroku haisukūruobuzadeddo akuto. 10.” Gakuen mokushiroku haisukūruobuzadeddo akuto. 10: Neko megane Second.N. P., 10 May 2007. U~ebu. 30 May 2017. http://nekomegane.seesaa.net/article/41294262.html. (A)

Nekomegane Second. “ Gakuen mokushiroku haisukūruobuzadeddo dai 3-kan.” Gakuen mokushiroku haisukūruobuzadeddo dai 3-kan: Neko megane Second. N. P., 6 Oct. 2007. U~ebu. 30 May 2017. http://nekomegane.seesaa.net/article/59065827.html. (B)

Oros, Andrew (ed.) (2008). Normalizing Japan. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Otmazgin N. and R. Suter (2016). Rewriting History in Manga. New York: Palgrave-MacMillan

Penney, Matthew (2007). ‘War Fantasy’ and Reality—‘War as Entertainment’ and Counter-narratives in Japanese Popular Culture. Japanese Studies, 27:1, 35-52

Perkins, Chris (2010). The Banality of Boundaries: Performance of the Nation in a Japanese Television Comedy. Television New Media. 11:5, 386-403.

Pippin, Tina (2010). “'Behold, I stand at the door and knock': the living dead and apocalyptic dystopia.” Bible and Critical Theory, 6:3, 40.1.

Purofīru gazō Sazae 1618. “ Netōyo-iro no tsuyoi shin'ya anime o oshietekudasai..” Yafū chiebukuro. N. P., 25 Mei 2012. U~ebu. 30 Mei 2017. https://detail.chiebukuro.yahoo.co.jp/qa/question_detail/q1187928196.

Sakamoto, Rumi (2011). “'Koreans, Go Home!' Internet Nationalism in Contemporary Japan as a Digitally Mediated Subculture” Japan Focus: The Asia Pacific Journal. 7.

Saft, Scott and Yumiko Ohara (2006). The media and the pursuit of militarism in Japan: Newspaper editorials in the aftermath of 9/11. Critical Discourse Studies, 3:01, 81-101

Sasada, Hironori (2006). Youth and Nationalism in Japan. SAIS Review. 36:2, 109-122.

Satō, Daisuke & Shoji Satō (2007). High School of the Dead. (Vol. 1-7). Tokyo: Fujimishobo.

Schodt, Frederik L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press.

Silverberg, Miriam (2006). Erotic Grotesque Nonsense. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stratton, Jon (2011). Zombie trouble: Zombie texts, bare life and displaced people. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 14:3, 265-281.

Taka, Fumiaki (2015). Nihongo tsuittā yūzā no chūgokujin ni tsuite no gensetsu no keiryō-teki bunseki - korian ni tsuite no gensetsu to no hikaku. Hito bungaku kenkyūshohō (Kanagawadaigaku hito bungaku kenkyūjo): 53, 73-86.

Tsuji, Daisuke (2008). “Internet ni okeru ‘Ukeika’ genshou ni kansuru jisshou kenkyu.”Chosa kekka gaiyou houkokusho. 1-40. (A)

———(2008). “’Net uyoku’ sei to ippanteki ‘Ukei’ sei tono kairi.” Osaka daigaku. (B)

Tsunehira, Furuya (2016). “The Roots and Realities of Japan's Cyber-Nationalism.” Nippon.com. N.p., 26 Jan. 2016. Accessed 10 May 2017.

Notes

[1] Otakuis a term used to describe individuals whose identity is subsumed into a narrowly focused interest in a particular hobby, often media. Buki-otakuis used to describe those who are interested in weaponry, especially firearms, or in the military.

[2] Netto-uyoku are members of the digital ultra-right. While previous generations of the ultra-right engaged in public action and semi-centralised organisations, these individuals tend to rely on digital resources and the internet.

[3] Like Billboard Charts for American music, this group tracks sales of mangain Japan.

[4] Satō Daisuke died due to heart disease on March 22, 2017.

[5] Red Sun Black Cross(Reddosen burakkucurosu).

[6] This prestigious award, named after the first great manga artist, is given to manga artists.

[7] Pornographic manga.

[8] Satō, Daisuke & Shoji Satō (2007). High School of the Dead. (Vol. 7). Tokyo: Fujimishobo. Pg. 3

[9] Moe refers to a semi-romantic, semi-filial attraction to a fictional character. These characters are often young girls, or shōjō.

[10] Tsundere is an archetypal personality, typically assigned to a female character, which describes her relationship to the protagonist, most often a male. A tsundereis one who rejects but still longs for the protagonist. Eyeglasses, particularly when worn by female characters, are considered a fetish for otaku.

[11] 2chan is a volunteer run Web-board that has been in existence since 1999. As the site lacks any form of user registration system, anonymity of its posters is virtually assured (McLelland 2008: 821).

[12] For example, in 2013, the American President, Barack Obama, forced a meeting between Prime Minister Abe of Japan and Prime Minister Park of South Korea at an international summit. Due to Prime Minister Abe’s perceived rollbacks of Japanese official apologies for the colonisation of Korea and pacifist policies (Delury 2015: 441-442).

[13] For more information on this phenomenon please see Bukh (2012).

[14] A garden ornament found in some traditional, Japanese gardens.

[15] The three highs were: high height, high education, and high income (Castro-Vazquez 2012: 100-101).

[16] Obtaining the right to own a firearm in Japan is a multistep process. One step involves a test that is held on a limited number of days each year and must be passed with a score of 95% or higher. Additionally, police will inspect the homes of gun owners on a yearly basis to ensure that ammunition and firearms are held in separate, locked boxes. This costly and cumbersome system ensures that only a limited number of persons ever obtain a firearm. That Kohta had firearm experience makes him exceptionally rare, even among buki-otaku(Low 2017).

[17] The author of Zero Senkōshinkyoku, a 1967 mangaabout Zero fighter pilots.

[18] The author of the major mangafranchiseSpace Battleship Yamato.

[19] The writer of a 1990 counter-factual Asia Pacific War with a technologically superior Imperial Japanese Army, developed thanks to a time-travelling Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku.

[20] She is a member of the Tokushu Kyūshū Butai, a shadowy organisation intended to augment police response to extreme threats, such as terrorist attacks or crimes with international implication like airline hijackings.

[21] Satō, Daisuke & Shoji Satō (2007). High School of the Dead. (Vol. 3). Tokyo: Fujimishobo. Pg. 3. Note the quote on the banner behind Takagi Soichiro is taken from Takamori Saigō, the notorious military leader who first assisted in the overthrow of the Tokugawa government only to turn against the following Meiji government as well. The image of violent, anti-establishment resistance is further emphasised by this historical allusion.

[22] This term can be translated as ‘the study of the Japanese people’; this field purports to analyse the emotional, cultural, or spiritual nature of the nation.

[23] A type of biker gang in Japan that is known for their coopting of Imperial Japanese military uniforms.

[24] Satō, Daisuke & Shoji Satō (2007). High School of the Dead. (Vol. 3). Tokyo: Fujimishobo. Pg. 5.

[25] Satō, Daisuke & Shoji Satō (2007). High School of the Dead. (Vol. 2). Tokyo: Fujimishobo. Pg. 30

[26] Satō, Daisuke & Shoji Satō (2007). High School of the Dead. (Vol. 3). Tokyo: Fujimishobo. Pg. 55.

Article copyright Barbara Greene.