Globalization and Women's Labour Activism in Japan

Volume 2, Issue 1 (Article 2 in 2002). First published in ejcjs on 6 December 2002.

Abstract

The concept of globalization not only encompasses increased economic integration and increased flows of capital, but also social, political and cultural change. While considerable attention has been paid to the pro-active role that Japanese government and business actors have played, there has been rather less analysis of the way civil actors in Japan have been affected by, and have adapted their goals and strategies to the changing global polity. This paper examines how female labour activists in Japan have adapted their strategies to the existing national and international institutions, and changed their strategies as the processes of globalization have altered the relative power of these institutions. Section B of the paper examines the lack of influence that women labour activists have traditionally had in party and trade union politics, and how changes in these institutions are affecting the way women engage with them. Section C looks at the alternative way campaigners for women's labour rights actually organize. Section D goes on to examine the way women's groups are increasingly directing action at international bodies, and sharing information and activities with activists overseas.

Introduction

The concept of globalization does not only encompass increased economic integration and increased flows of capital, but also social, political and cultural change. While considerable attention has been paid to the pro-active role that Japanese government and business actors have played in the globalization of production (Hasegawa and Hook, 1998, Hatch and Yamamura, 1996), there has been rather less analysis of the way civil actors in Japan have been affected by, and have adapted their goals and strategies to the changing global polity.

Cox has observed that there has been a revival of civil society as a response to globalization. He cites the French strikes of 1995 and the South Korean protests of 1997, and the growth of NGOs in Japan and other Asian countries, which often build links and mutual aid relationships with similar organizations in other countries, and distinguished between 'top-down' activity where states and corporate interests can try to co-opt civil society and encourage actors towards conformity and 'bottom-up' action, in which civil society acts as a conduit for those disadvantaged by globalization to mount protests and propose alternatives (Cox, 1999). This paper will describe the latter process, taking as an example the women's movement in Japan.

Several changes associated with social and political globalization have facilitated the development of feminism. These include the increased salience of non-state identities (Mann, 1997); the opening up opportunities for effective political activity at a local level (Strange, 1996); a raised the international profile of women's rights (Keck and Sikkink, 1998, Ariffin, 1999, Bayes and Kelly, 2001); and the potential for activists to use international law and organize transnationally (Costa, 1999).

Globalization has certainly impacted upon women's activism in Japan, as this paper will illustrate. However, the strategies pursued by supporters of Japanese women workers are also partly shaped by the institutions of Japanese governance. These institutions include a political party and trade union system, which is constituted in such a way that women are effectively excluded, and a homosocial normative order, which dictates that activism is usually structured along gender lines. This paper will examine how female labour activists in Japan have adapted their strategies to the existing national and international institutions, and changed their strategies as the processes of globalization have altered the relative power of these institutions. Section B of the paper examines the lack of influence that women labour activists have traditionally had in party and trade union politics, and how changes in these institutions are affecting the way women engage with them. Section C looks at the alternative way campaigners for women's labour rights actually do organize: through active networking, using Women's Centres, and publishing minikomi, before Section D goes on to examine the way women's groups are increasingly directing action at international bodies, and sharing information and activities with activists overseas.

Women in electoral politics

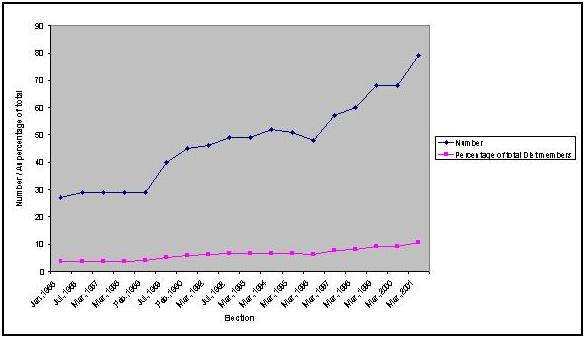

This section will show how the institutions of Japanese politics have been difficult for women to penetrate, therefore encouraging extra-parliamentary activism. However, one of the ironies of democratic representation and globalization is that, just as the power of the nation state is declining (Held, 1995), the proportion of liberal democracies and the number of female parliamentary representatives is increasing (Walby, 2001). This has been the case in Japan, as Figure 1 below shows.

Another observation commonly made about globalization is that governance has become more multi-layered as policies are increasingly formulated at a sub-state or suprastate level (Strange, 1995). Women activists in Japan have, in recent years, concentrated their activities at the local state level, or, as shown in Section D, at the transnational level.

Political representation

In Japan's first post-war election 39 female deputies were elected out of a total of 464, a proportion of more than 8 percent. However, as figure one shows, this proportion was not equalled for some decades. The majority of the female candidates represented the left or centre-left, meaning that, when the Japanese political system was reformed, in 1947, changing from large to medium-sized electoral districts, this disadvantaged the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Japan Communist Party, and consequently female left-wingers lost their seats. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)'s political priority, and undoubted success was Japan's economic growth. With this end in mind, its election tactics consisted predominantly of establishing strong links with the corporate elite, an elite from which women were largely excluded. Ideologically also, the LDP did not appear keen to encourage female candidates and for one period of ten years had no female deputies at all.

Even within centre left parties, however, there were institutional reasons why women were less likely than men to be selected. With the exception of Doi Takako, who became Japan's first female political party leader in 1986, female SPD candidates were only successful if they had the support of trade unions. Women account for only 28 per cent of trade unionists in Japan (Miura, 2001) and with the decline of union membership in the 1970s, the number of Diet seats fell, so there were fewer seats available. Ironically, the decline in political influence of trade unions may also have negatively affected the proportion of women standing. In the past unions used to undertake to support unsuccessful candidates, whom they sponsored, until the next election. Now this is less and less frequent, so only those who are either financially secure, or very sure of winning, can afford to stand. This disproportionately disadvantages women, who are less likely to be able to garner electoral funds and are less likely to be elected.

The contribution of social norms may also play a part in excluding women from parliamentary power. Voters are, at first blush, apparently reluctant to vote for women. In the general election of 25 June, 2000, only 17 per cent of women who stood for election were returned, compared to 37 per cent for men (Mikanagi, 2001). However, this also raises the question, as in the UK, of the extent to which women are allowed to contest winnable seats.

As well as the institutional factors working against women, Mikanagi (2001) attributes the lack of representation of women's interests in the formal political sphere to the characteristics of those interested in feminist politics. Particularly she decries the influence of radical feminism in Japan - a brand of feminism, she claims, that has encouraged Japanese feminists to keep a distance from the 'patriarchal state'. Campaigning for equal labour rights, in the 1950s to the 1970s, appeared to have a lower profile than anti-nuclear and environmental women's movement, according to Eto (2001). This was because, as Japanese women's labour market participation at this time was less than in Europe and the US, Japanese women were less conscious of the gender-based division of paid labour than their Western counterparts.

A variety of women's groups have, however, been active in lobbying the government. In particular the administrative reforms of the mid-1980s, where the Nakasone government cut education, welfare and environmental spending, excited the anger of women's groups. Cuts in decreased spending for day care centres and school lunches, which increased the reproductive work done by women, were particularly controversial. In 1981 cutbacks were introduced in public service provision, and in 1982 a group of women who have been forced to leave their jobs or give up social activities because of increased caring obligations held a symposium to publicize this issue in Tokyo (Eto, 2001).

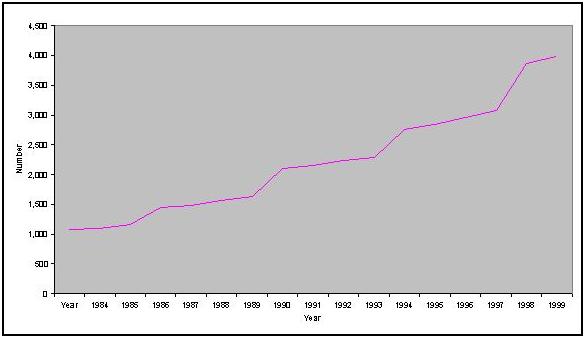

Electoral and parliamentary institutions in Japan, then, have generally been male-dominated, and, perhaps as a result of this, have tended to pursue policies which work to the detriment of female workers. Institutions and social norms are however dynamic. The introduction of new ideas through the intervention of the United Nations, and its associated conventions and conferences, which were followed by an upsurge in feminist activities in Japan, and an increased awareness of issues of gender equality in the general population. The increased representation of women in the Diet and local assemblies (Figures 1 and 2) is a sign that Japanese voters are more willing to accept female politicians. Women's rights activists are taking advantage of this by increasingly attempting to enter formal political institutions. Furthermore there are signs of representatives making positive efforts to recruit more women. In February 1992 the Feminists Assemblymen's (sic) Federation, whose membership is made up of 65 female and 5 male national and local government representatives, resolved to campaign for a membership quotas of 30 per cent for women in each prefectural assembly (Iwao, 1993).

Women's traditional marginalization from electoral politics, can give them the freedom to act more independently, once they gain a seat in Parliament. Moriya Yuko, the founder of a school for female politicians, claims, 'Women do not feel restrained to ask questions in the assembly. This stimulates their male colleagues to ask more questions. Thus a more open style of decision making is being implemented rather than the elitist "over-dinner-and-drinks" sort of decision-making style.' (Foreign Press Center, 2001). Certainly, Ms Doi was criticized by male politicians for her blunt 'unfeminine' style; and Tanaka Makiko, the foreign minister, who lost her job in a high profile sacking on 29 January 2002, was fantastically popular with the general public for her outspoken and flamboyant style.

Figure 1. Figure 1: Women Diet Members, Jan 1988 - March 2001

Source: Cabinet Office, 2001

Figure 2. Number of Female Local Assembly Members

Source: Cabinet Office, 2001

A 1991 study by the Center for the American Women and Politics at Rutgers University found that regardless of party or ideology female politicians tend to have a different agenda to men (Fujimura-Fanselow and Kameda, 1995: 373). Women in the Japanese assemblies do seem to be perceived as being allied to a feminist agenda. In 1992 the National Federation of Feminist Legislators was established as a non-partisan national network of 130 male and female legislators with an interest in feminist concerns.

There are nearly thirty extraparliamentary women's groups, which aim to put women's issues on the Japanese political agenda. Most of them are activist groups. Some support specific candidates, while others aim to raise the profile of women's issues. Onna kara Onnatachi e: Ichinichi Jūen no Kai (From Woman to Women: Ten-Yen a Day group), for example, has the goal of electing a female district councillor to focus on women's issues (Khor, 1999)

According to Women 2000: Japan NGO Report, however:

One of the serious obstacles to create (sic) a gender equality society is the ignorance of gender issues among local government officers and members of local assemblies. Local government officers have to obey decisions made at assemblies. Therefore, consciousness raising of those officers and assembly members by gender training is important. Consciousness of the civil society itself which elects those assembly members should also be raised. (Japan NGO Report Preparatory Committee, 1999: 67)

However, according to the theory of institutional dynamism, one of the catalysts for institutions to become dynamic is that changes in the socio-economic context or political balance of power produce a new situation where old institutions begin to serve different ends as new actors gain a foothold within them (Thelan and Steinmo, 1992). This has certainly been the case in Japan, where local governments have come to be champions of initiatives towards gender equality as, supported by women's networks, feminist deputies gain representation.

In June 1999, the Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society came into effect. Like the Equal Employment Opportunities Law, the Basic Law was the indirect outcome of Japan's participation in UN initiatives, and Chapter Four of the Law states the intention of [a]dopting and absorbing international standards in Japan' (Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office, 2000). The Platform for Action of the Fourth World Conference on Women called for governments to develop plans of action for gender equality. The Japanese Council for Gender Equality submitted its report, 'Vision of Gender Equality - Creating New Values for the 21st Century' to the Prime Minister on 30 July 1996. This was followed by a new national plan of action entitled 'National Plan for Gender Equality toward Year 2000' on December 13, 1996.

The aim of the Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society was to clarify basic concepts pertaining to formation of a gender-equal society and indicate the direction these should take. Under the Law, the central government, local governments and Japanese citizens are required to make efforts toward the achievement of a gender-equal society in all areas. Under the auspices of the Act, in Tokyo the local government can request private companies to report on the status of their implementation of gender equality (Hashimoto, 2001) . Gifu prefecture has conducted research on the sexual division of labour in the workplace and in the home, and Fukui City has concentrated on improving women's political participation.

The diffusion of power to local assemblies, has resulted in the entirely pragmatic decision by feminist activists to deliberately target local government. Strategies include joining advisory committees or attempting to aid the election of candidates who will champion feminist causes. Moriya Yuko worked for 20 years after university graduation, and in that time came to feel that women would be empowered if they entered the decision-making fields from which they were largely excluded. In 1993, she resigned from her job in research and planning and launched the 'Society for Discussing Women and Politics'. However, she was further radicalized by her participation in the World Conference on Women in Beijing, where she was 'stimulated by the energy of assembly women from the West and elsewhere' (Foreign Press Center, 2001).

In 1996 Moriya set up the 'World Women's Conference Network, Kansai' to promote international exchange among women, and founded a school for aspiring female politicians. This non-profit making organization (NPO) based in Osaka is run by Fifty Net, which aims to achieve a situation where fifty per cent of councillors are women. Two hundred women applied for the initial 30 places to learn about policy-making, the workings of parliament and know-how regarding elections from lectures by politicians and women's activists. Seventy-four were accepted, and by 2001, 25 graduates of the course had become councillors.

Nonetheless, in 2000, the United Nations Gender Empowerment measure, which records women's participation in political and economic decision-making, still ranked Japan only 41st out of 70 countries judged to have 'high human development' (United Nations Development Programme, 2000). And ironically, just as women are organising to take advantage of changes in political awareness in Japan, which might permit women to formal political power, opponents of neo-liberal economic globalization are arguing that concentrating on conventional electoral politics is futile, where the main parties accept the discipline of global capital (Falk, 1997).

Women in trade union politics

An obvious avenue to campaign for women's labour rights is through the trade union movement. However, women account for only 28 per cent of the membership of Japanese trade unions. After the deflation of the 1940s unions moved from including all non-managerial employees to a membership limited to those whose job security was assured. The corollary of this is that as non-regular forms of employment have increased, the proportion of labour which is unionized has fallen from around a peak of 34.4 per cent in 1975 to an all time low of 22.2 per cent in 1999 (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Dec 24, 1999).

Some unions have recently made an effort to recruit non-regular workers. Part-timers account for 24.3 per cent of the membership of the Japan Federation of Commercial Workers' Union (Shōgyō Rōren) and 17.4 per cent of the National Union of General Workers (Zenkoku Ippan) respectively. However, other unions, even in highly-feminized sectors recruit few part-timers. Only five per cent of members of the Japanese Federation of Textile, Garment, Chemical, Food and Allied Industries Workers' Union (Zensen) are part-time workers. Rates of unionization of dispatched workers are even lower (Miura, 2001).

One response to the lack of female representation in mainstream unions has been the formation of small independent, predominantly female, unions. Tokyo Josei Union was established in March 1995. It has 18 committee members and charges a membership fee of 2,000 yen per month. Between its establishment and July 1999, the union has recorded 3,383 consultations from women, mainly concerned with restructuring, and change of status from regular to non-regular status. The union operates by recording women's complaints on their Working Women's Helpline. They then encourage the complainant join the union and to fill out an application form for 'collective bargaining' with the company. According to the union most collective bargaining actions are completed within six months. In the period covered, Tokyo Josei Union had dealt with almost 200 cases, of which the majority were resolved by compensation and continued employment (Tokyo Josei Union Newsletter, 1999).

Japanese feminist movements

Extent and nature of group membership

The above sections have demonstrated the reasons why formal politics has been a largely male preserve. Women, who are politically active, tend to be politically active in a realm outside the male formal polity.

The fact that Japanese cultural norms often structure activism and political participation along gender lines, means that women's social and political life is often organized around women's organizations, which provide an autonomous basis on which to challenge women's exclusion, and to challenge the existing political hegemony. Passy (2000) claims that networks fill a vital gap between structure and agency in that they socialize and build individual identities; recruit individuals who are sensitive to a particular political issue, and allow them the chance to participate; and shape individuals' preferencesbefore they decide to join the movement.

Although this paper emphasizes the importance of outside influences, networks and the use of foreign institutions to put pressure upon the Japanese government, Japan has a long-standing of indigenous women's movements. Just after the 1880s popular rights movements stimulated strikes by female workers. The 1920s saw the emergence of an active women's suffrage movement that succeeded in getting a Bill passed in the House of Representatives that gave women the vote in 1930, but the House of Peers session ended before it could be ratified and, with the Manchuria Incident in 1931, and subsequent events, it became indefinitely postponed (Iwao, 1993). During the Second World War, women's activist groups were either banned or co-opted: the women of the Greater Japan Women's Patriotic Association (Dai Nippon Aikoku Fujin Kai), for example were active in supporting Japan's war effort (Fujieda, 1995). The Occupation Forces were keen to encourage women's emancipation and a new women's movement, associated with progressive, labour-related policies emerged. Its connections with the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) however caused disquiet in SCAP, and the administration tried to revive the old community groups association with the Patriotic Association, and 'rehabilitate' its leaders after some cursory 're-education' (Matsui, 1996: 24). This seems to be a clear example of attempts at top-down organization of civil society. There were therefore two major strands to the women's movement in the immediate post-war period. The JCP Central Conference on Working Women movement clung to the Marxian idea that the oppression of women would be solved with the achievement of a socialist society, and thus concentrated on organising women into trade unions, rather than analysing or protesting against the more complex conditions of women in post war Japan (Tanaka, 1995). The rump of the Central Conference on Working Women is however still active today, particularly in campaigning for part-time workers' rights (Zenroren, 1997). There was also a more conservative network of women who organize non-challenging cultural activities, such as taking language or cookery classes. The latter were supported by women's centres called Fujin Kaikan, usually built by public organizations and operated by local women's groups. By 1960s there were more than 100 private and state Fujin Kaikan.

There was little high profile activism around women's labour rights until the 1970s, when the ūman ribu (women's lib movement) burst into public consciousness on 21 October, 1970, when ūman ribu marched in the streets of Tokyo carrying placards, with such slogans protesting about a range of issues. Placards read, 'Mother, are you really happy with your married life?', 'A Housewife and a Prostitute are Raccoons in the Same Den.' (Tanaka, 1995). The majority of the ūman ribu activists were disillusioned young female workers and students who had been active in the New Left, anti-Vietnam War movements, and had been dissatisfied by the cognitive dissonance of male activists who rejected authority, yet permitted female activists only such stereotyped roles as typing. Some ūman ribu activists experimented with collectives for women and children, consciousness-raising groups and staging high profile 'zapping' activities, such as targeting individual men at their places of work. Several of the ūman ribu activists participate in the feminist movement even today. However, their high profile activities, such as marching in pink helmets, demanding the legalization of the contraceptive pill, while attracting significant media coverage, were often ridiculed and attracted little public sympathy.

Nonetheless ūman ribu did reflect a growing interest in women's issues at the time. This had been occasioned by the following:

- Economic growth leading to women's greater participation in the workforce. An increasing number of women therefore were bearing the double load of paid employment and household chores (Tanaka, 1995). A number of academics, such as Komatsu Makiko, became interested in the problem of women in the labour force, and of sexual discrimination in the workplace.

- The establishment of academic women's studies. Female academics that had studied in the US or Europe returned to Japan and introduced women's studies in the Japanese Academy. Japan Fujinmondai Kōwakai member, Inoue Teruko member introduced the ideas discussed in 'Women's Studies' in the US as 'Joseigaku'. Iwao and Hara wrote a book called 'Joseigaku nyūmon' (Introduction to Women's Studies). (Komatsu, 2002: personal communication)

The groups which emerged in the second half of the 1970s, and were more likely to be lawyers, Diet members, labour movement activists and members of political parties, were more directly focussed on 'working within the system' and influencing government policies and actions (Tanaka, 1995). They were lent more legitimacy in the eyes of the public and among elites when the UN International Women's Year forced the Japanese government act on the problem of sex discrimination. In 1975 the Japanese government set up the Headquarters for the Planning and Promotion of Policies related to women. Fifty-two NGO groups came to make up the Liaison group for the Implementation of the Resolution from the International Women's Year Conference on Japan (Kokusai Fujin-nen Renraku-kai).

Sperling, Ferree and Risman (2001) have cited the case of Russian groups who intentionally use the language of international organizations to gain legitimacy for their own struggles. This tactic is also employed by some Japanese women's groups. The UN is extremely well regarded in Japan, and therefore campaigning using UN documents, protesting at UN conferences have proved to be effective strategies for women's groups with little formal influence at the domestic level, a strategy referred to by Keck and Sikkink (1998) as a 'boomerang' strategy. Attending the UN Women's Conferences has also proved to be inspirational on a personal level to several activists whom I interviewed.

Although Japan was not permitted to join the United Nations until 1956, the Women's and Young Workers' Bureau of the Ministry of Labour, impressed with the UN Commission on the Status of Women, has been sending observers since 1950. The United Nations Decade of Women (1975-1985) and International Women's Year (1975) also stimulated much popular and media debate in Japan, and impacted upon public opinion (National Institute of Employment and Vocational Research, 1988). In the late 1970s the Japanese government established the National Women's Education Centre and the 1970s and 1980s saw state-led building programmes of women's centres. These have proved to be more of a focus for overtly feminist activities than thefujin kaikan. This is indicated in the choice of name: josei sentā, rather than fujin kaikan. While josei and fujin both mean 'woman', the Chinese character 'fu' depicts a woman carrying a broom, and therefore does not indicate a challenge to traditional roles for women.

In July 1985, 27 delegates, led by the Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs; 13 advisory female Diet members and 700 NGO members, who were to attend the NGO forum, went to Nairobi to the UN conference where the Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women was passed. Professor Komatsu Makiko has long been active in campaigning and research on women's labour issues, and wrote the second ever women studies textbook in Japan. She told me about the effect the conference had on her, by encouraging her to be active and introducing her to feminists from other countries:

Interviewer: Did International Decade of Women have a high profile in Japan?

Komatsu Makiko: Yes, because the Japanese government began to develop Gender Equality Policy from 1975, the year of the first UN conference on gender equality in Mexico City.

Interviewer: Did you go?

Komatsu Makiko: No I didn't go. The second time I went - to Nairobi.

Interviewer: What were your impressions?

Komatsu Makiko: That's so vigorous, brilliant and [...] Power! (Interview, 19 January, 2001)

She added that she had been deeply impressed by 'the power of African women' and had come to deeply consider the relation between multi-culturalism and human rights.

The year before the UN conference in Beijing, the Japanese government established the Headquarters for the Promotion of Gender Equality, within the Prime Minister's Office, with the function of 'gender mainstreaming', integrating a gender equality perspective across all areas of government policy (True and Mintrom, 2001). Approximately 6000 Japanese women attended the Beijing Conference (CEDAW, 2000). Moriya Yuko, founder of the school for female politicians, referred to earlier, said,

It was the Beijing Conference in '95 (the 4th World Women's Conference) that made me start the network. I saw many women involved in the political scene before my eyes and I thought, 'Hey, we need this in Japan too!' (Moriya, 2001, in WINGS)

After Beijing, attendees from Japan set up new NGOs and pushed for national and local governments to work in accordance with the Beijing principles. One of the highest profile groups is the Beijing Japan Accountability Caucus (Beijing JAC), with branches in Tokyo, Kansai, Hiroshima, Sendai, Shizuoka, and Yamaguchi. The World Women's Conference Network, Kansai, was begun in 1996 by Kansai women, who had attended the Beijing conference, to 'make good use of the results of the conference and to enlarge the public role for women'.

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women was the catalyst for the passing of the Equal Employment Opportunities Law (EEOL). The Japanese Association of International Women's Rights (JAIWR) developed various programs to publicize the Convention, which Japan agreed to ratify in 1980. JAIWR's programs are based on drama performances and questionnaires to check one's gender bias. Twenty years after the Convention was signed, the term CEDAW was known to 37 per cent of a July 2000 survey conducted by the government for the July 2000 White Paper on Women (compared to only 13.6 per cent who had heard of 'affirmative action' and 7.1 per cent who understood the concept of 'unpaid work', Dales, 2001).

Unlike ūman ribu, the new groups tended to be more oriented towards single issues. There is no Japanese equivalent of the American National Organization of Women. However, groups do tend to be long-lasting and active, usually meeting frequently and producing minikomi. Kohr (1999) analysed 590 groups from an initial list of 1000 on the Onna no Nettowākingu (Women's Networking) list for Japan. About 50 per cent, she found, could be classified as activist. However I would contend that 'research / study' groups on the list also play a role in creating pressure for change, and conducting independent research seems to be a core activity for groups in Japan. A group of lawyers and academics calling themselves the Women Workers Research Group (Fujin Rōdōsha mondai kenkyūkai) reported that 80 per cent of women surveyed in 1988 said the EEOL had had little effect on their workplace (1995). The Part-Time Work Research Group to Consider Women's Working Life conducted a survey of 2319 working women (excluding dispatched workers) and liaises and shares information with other women's labour organizations elsewhere in Asia. Furthermore, one of the most high profile activities of the women's movement is the publication of Counter-Reports to Japanese Government's Periodic Reports to CEDAW in July 1994 and August 1999 (A Letter to Japanese Women, 1994 in Japan NGO Report Preparatory Committee, 1999). Countries that have ratified or acceded to the Convention are legally bound to put its provisions into practice, and to submit national reports, at least every four years, on measures they have taken to comply with their treaty obligations. In March 1999, after the 43rd sessions of the Commission on the Status of Women in New York, with news from the Conference of Non-Governmental Organizations (CONGO), that while there would be no NGO Forum at the Women 2000 Special Session of the UN General Assembly, 'NGOs are encouraged to compile an alternative report on their country's implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action.' Twelve organizations in Japan obtained responses from 300 organizations and individuals and finalized the report at a public meeting.

There is also a general expectation that those involved in research about women should be committed to the women's movement, and that 'women's studies' should not be an elitist, narrowly-academic pursuit. The Women's Studies Association of Japan (Nihon Joseigaku Kai), for example, was formed in 1978, and has 600 members, including researchers, students, housewives and company employees (Worldwide Organization of Women's Studies, 2000; Khor, 1999) Several of the groups have a dual focus: perhaps particularly specific to Japan are English discussion groups, whose members initially come together to discuss current topics in English. Members are recruited, perhaps to discuss current events in English, and in an all-female group undergo a process of socialization/consciousness raising, which leads to the group or the individuals becoming keener to be involved in activism.

Women's Messages, for example, is a discussion, study and publishing group, which was founded in 1988. Its members come together to discuss topical news articles in English on a bi-weekly basis, as well as hosting talks about 'world issues' and 'women's issues'. The magazine is sent to about 600 individuals and organizations in 87 countries and highlights sex discrimination in the Japanese workforce as well as forging links with, and supporting the campaigns of, women's groups overseas (Usui, 2002). Usui Yuki joined Women's Messages to practise her English language, but became increasingly interested in the articles she read. She is now a regular contributor, and translator to the Women's Messages Newsletter (ibid) and eventually went to Dublin to take an MA in Women's Studies. She now is very involved in Working Women's International Network and Women Helping Women.

Similarly, the English Discussion Society similarly has published two books, Japanese Women Now (English Discussion Society, 1993), and Japanese Women Today Two (English Discussion Society, 1996), in which they provide previously unavailable information about the situation of Japanese women in the home and in the workforce, in English.

Kohr (1999) notes that there are 50 groups, which are concerned with women's employment. Around 50 per cent of these provide support for part-time workers re-entering paid employment, while the other half are 'activist' groups which aim to redress issues of discrimination, balancing productive and reproductive work and issues of sexual harassment. There are, according to Kohr (1999) a further 50 groups concerned with women's businesses, either pragmatically to create work which fits in with domestic labour, or to challenge male domination of paid work, by offering flexible work hours, provide services or teach women such traditionally 'male' skills as refurbishing.

Many of these women's groups make use of the josei sentā to meet for 'Self-enlightenment and teaching, collection and distribution of information, consultation, surveys and research, exchange of views among individual women and groups.'(Uno, 1997: 2). While in Japan, I frequently attended meetings, seminars and lectures at one such josei sentā, the Dawn Centre in Osaka. This 11 storey building was established in November 1994 by Osaka Prefectural Government under the administration of the Osaka Gender Equality Foundation. It is open six days per week from 9.30 am to 9.30 pm and attracted nearly one million people in its first two years. While some feminist groups were less than enthusiastic about the women's centre building programme, complaining for example, that there was a greater need for refuges for women fleeing domestic violence (Uno, 1997), in recent years, women's activists, rather than being co-opted by the relatively institutional nature of the women's centres, have used them for explicitly feminist aims.

Usui Yuki told me:

They [women's centres] help work effectively to play a supportive role, because they have places, so lots of women can have a meeting there and also lots of events are organized. So ... the thing is these women's centres are all over Japan, and their policy or strategy is greatly affected by the boss ... top people's awareness ... understanding.

She agreed that josei sentaa are not necessarily feminist, but added

... recently a lot of NPO groups, women's groups, specially if they have power in local area, then this government or this gyōsei[adminstration] contact this group to get some idea from the group, because they don't know well about their strategies ... So this kind of situation happens quite a lot. Actually I was asked by one of the josei sentās to talk about the issues of organising women's centres.

As the Centres are a focus for women, activists can even make use of physical proximity to the Centre. Three lawyers that were active in the Kintō Hō Network have recently formed an independent practice situated in front of the Dawn Centre, where women can consult them on their labour rights.

The Globalization of Women's Activism

As well as using an international stage as a base for campaigning, Japanese women's groups have built links with other women's labour campaigners to add to foreign pressure on the Japanese government, to pragmatically share information and to build solidarity with women workers elsewhere in the world. From the 1970s women's groups in Japan and in other Asian countries have organised jointly to protest about Japanese sex tours to countries hosting Japanese FDI. In 1995, the Asia-Japan Women's Resource Center was established in Tokyo to extend and provide a basis for the activities of the Asian Women's Association (AWA), one of several women's organizations in Japan which has adopted a critical view of Japan's role in Asia since the 1970s. It acts as a bridge to link Japanese women with women's groups elsewhere in Asia in order to share information and engage in joint activities around the issues of migrant women, prostitution and trafficking of Asian women, Asian brides and international marriages, Japanese - Filipino children, and women workers employed by Japanese multinational companies.

Another example is transnational activism around sexual harassment. Japanese women's groups, in 1996, sponsored the week-long visit to Japan of the US National Organization of Women (NOW)'s Vice President Rosemary Dempsey. The aim of the trip was to raise awareness of sexual harassment. The more than 50 Japanese groups involved also intended to show solidarity with US women workers who had filed sexual harassment charges against the Japanese MNC Mitsubishi Motor Manufacturing. It seems indisputable that gaiatsu (foreign pressure) enabled the feminist groups to win their case. Dempsey met feminist groups, business leaders, parliamentary representatives, trade union leaders, the Minister of Labour and representatives of Mitsubishi. The visit was widely publicized and the Minister of Labour reversed his previous stance and came out in support of a tougher EEOL, which included prohibitions on sexual harassment (Corbin, 1996).

Prior to World Conference on Women in Beijing, several regional meetings were organized in Asia. At the Asia Pacific NGO Symposium held in Manila in 1993, women from East Asia held a regional workshop which resulted in the formation of the East Asia Women Forum, with the first meeting held in Japan the following year. This was rather significant as

Despite the fact that women in East Asia share the experience of the rapid economic growth in the region, the common cultural background of Confucian patriarchy and the history of Japanese military rule, it was the first gathering of activists from different women's groups in East Asia. (Moriki, 1997. pp.1-2)

Women's activists became increasingly aware of the link between their own situation and the globalization of Japanese production. In fact, one of the rationales for opposing the revision of Labour Standards Law was that regulations would be similarly relaxed in Japanese companies overseas, as this extract from the 1999 Counter Report to the UN makes clear:

In addition, we are afraid the abolition of the restriction for the protection of female workers will have a bad influence on Asian Women Worker's working conditions. It is necessary to watch carefully that the working conditions of Asians does not worsen in Japanese enterprises. (Japan NGO Report Preparatory Committee, 1999: 51)

Similarly Shiozawa Miyoko, Director of the Asian Women Workers' Center explained her hesitation to write 'Stories of Japanese Women Workers', as a companion volume to the publication of stories of Korean and Filipino working women, as she felt that the vast material differences between the lives of women in Japan and those elsewhere in Asia would make it difficult for women outside Japan to appreciate the difficulties women in Japan faced. However she decided to contribute to the book, because she believed that not only were women workers in Japan subject to the double burden of responsibility for housework and childrearing, in addition to a job outside the home and discrimination, meaning that 'although their suffering may be mitigated by enjoying occasional extravagances, their human growth is seriously hindered, probably in a way very different from our Asian sisters' (Shiozawa, 1988: i). This, added to concern that 'the Japanese method of labour control, which is becoming increasingly sophisticated and is now being introduced into Asian countries through Japanese-owned corporations', and the trade friction caused by long working hours and labour intensity, causing the market expansion of export-oriented low-cost projects convinced her that

... the struggle for liberation from the bitter exploitation of capital is common and can be shared, although the forms of struggle may be different in each country (ibid: ii)

Again, groups in Japan have attempted to raise consciousness through research and publicity. The Association of Asian Women (Ajia no onnatachi no kai) between 1977 and 1991 published the Ajia to josei kaioho (Asia in Everyday Life), in which they considered food, cosmetics, and manufactured goods produced in Asia and brought to Japan so that Japanese women could see the way in which they were direct beneficiaries of exploitation of their Asian sisters. Other editions of Ajia no Kaiho focussed on political repression in Asian countries; Japanese cultural imperialism; liberation movements in Asian countries; the economic activities of Japanese companies in Asian countries; and international tourism industry and its links with prostitution (Mackie, 1999). The emergence of the ethical consumer is perhaps a sign of the links between the economic and cultural aspects of globalization.

Recently such organizations as the Asian Women's Association have paid attention to Japan's role as a major donor of foreign aid in the region and the increased emphasis on support for tourism-related projects.

Working Women's Network: An example of an activist group

Working Women's Network (WWN) has a long history. It started in October 1995, having grown out of a smaller group (Kintō Hō [EEOL] Network) which was set up in 1986 to discuss and raise awareness of the EEOL. Kintō Hō Network itself grew out of a study group with an interest in women and labour issues. In 1995 around 100 women came together to form WWN in support of core members who were suffering from discrimination in the workplace. WWN's inaugural meeting at the Osaka Dawn Centre attracted a large number of company workers, civil servants, lawyers, researchers, and the organization now has a membership of over 800. WWN is currently supporting the core members, who are plaintiffs in a number of sex discrimination cases against various branches of the Sumitomo Corporation.

Members commit a great deal of their own money and time to the organization. The Japanese government report to the International Labour Organization that women in Japan earned on average 80 per cent of average male earnings was countered by a visit of 12 WWN members to give evidence to the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations of the ILO in September 1997 with their own statistics and information about their cause. The same month the delegates made representations to the United Nations and the European Union (WWIN 2001a). These activities were well-covered in the Japanese press, as was the visit of Dr. Marsha A. Freeman, Director of the International Women's Rights Action Watch, who, at the behest of WWN, in 1999, submitted to the Court her statement on the following issues in the case of Shirafuji Eiko and Nishimura Katsumi versus Sumitomo Electric and the Government of Japan. The Japanese government had claimed that Japanese tradition was an obstacle to the immediate implementation of CEDAW, and argued for a culturally-based gradualist implementation of the standard of sexual equality in the workplace, while Dr. Freeman pointed out that the language of the convention required immediate implementation of the non-discrimination provision (WWIN, 2001).

WWN is backed by a subsidiary organization, Working Women's International Network (WWIN), consisting of Japanese activists and a fluctuating number of foreign women living in Japan. When I attended there were usually about 10 members and Dales (2001) reports that there are now around 7 regular attenders. Meetings are conducted in English and Japanese. Foreign members were encouraged to network with people in their own countries to collect signatures from overseas for a petition supporting the Sumitomo women. The movement also produces an English version of their minikomiWorking Women's International Network: A Message from Japan, which mainly provides details of the progress of the court cases. WWN places a high value on using international exposure of the Japanese situation to attain their goals. Usui (2002) told me:

They organized a symposium about informal discrimination ... indirect discrimination and I think speakers from abroad came to Japan and did several symposiums. Also ... yeah, I think these kind of symposiums to deepen the understanding of women's working situation, and especially they have a network with other countries, because their activities is introduced in foreign countries too. For example they brought a counter-report of their working situation, which is totally different from the government report, so they brought this to New York and revealed the situation ... it was a kind of gaiatsu (foreign pressure), because Japanese government or Japanese legal system does not deal with these issues seriously, so women go abroad directly and appeal more sympathetic organization in foreign countries, and then they give some comment to the Japanese government. [This] embarrass[es] the government quite a lot. ... it gives the impact, so in that sense their strategy to appeal to the outside of Japan organization has a great impact to raise the awareness ...

I asked about the size of audiences at symposia, and Ms Usui claimed that, depending on the size of the meeting room, meetings attracted up to 450 participants. Despite their efforts, those court cases, which have so far been decided have ultimately resulted in defeats for the plaintiffs. However they did mount a striking protest, hiring a helicopter to advertise their protest and then forming a human chain around the courthouse. This too was covered on television and in the newspapers.

Conclusion

Campaigners to improve the position of working women in Japan are active and well-informed. However, the institutionalism sexism of the parliamentary system and the mainstream trade union movement, as well as the homosociality of Japanese society, means that formal politics has not been the main means of engagement for politically active women. There are signs that Parliament and local government are opening up to women, and those women who have entered formal politics have tended to have both a high profile and a feminist agenda. The impact of economic globalization in causing Japanese corporations to alter their employment practice, legislators to pass laws facilitating this has been well-documented (Hasegawa and Hook, 2001; Dore, 2000). However the processes of political globalization, including the development of supranational governance, transnational activism, and foreign pressure (or at least the perception of foreign pressure) have also affected Japanese government policy. Particularly, Japanese national and local governments have passed more rigorous sex discrimination legislation and built a physical network of women's centres.

Although these changes are making electoral politics more accessible than previously, most campaigners for women's labour rights continue to concentrate on activities within women's groups. Their aims are typically to raise public awareness of women's disadvantage in the workplace and to campaign for tighter regulation of companies. There is a perception within these groups that Japan's high degree of involvement with international organizations and the positive view in Japan of internationalization can work to women's advantage. This is to some extent a correct perception as Japan's equal opportunities legislation and increased public awareness of women's labour rights are strongly associated with the United Nations and the ILO. Women's groups are increasingly working with their counterparts overseas both to share information and also out of a feeling of national responsibility towards the situation of women workers in Asia.

The example of Working Women's Network shows several characteristics of a Japan women's activist group. It is of long duration and core members combine research with protest, and place a high priority on creating effective international links. It makes use of institutional facilities for women, and is exercising an increasing influence within Osaka Dawn Centre. It has been successful in recruiting members and publicising issues, but has not, as yet, achieved direct success in achieving its goals.

References

Ariffin, R. (1999) 'Feminism in Malaysia: A historical and present perspective of women's struggles in Malaysia', Women's Studies International Forum, vol. 22, no. 4, pp.417-423

Bayes, J. and Kelly, R. (2001) 'Political Spaces, Gender, and NAFTA' in Kelly et al., pp.147-170

Cabinet Office (2001) 'Policies to be Implemented in FY 2001 to Promote the Formation of a Gender-Equal Society', Tokyo: Cabinet Office, downloaded 1/11/2002

CEDAW (2000) Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, New York: United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women, downloaded 30/09/2002

Corbin, B. (1996) Global Campaign Aims to End 'Seku Hara': Protests by U.S. and Japanese Feminists, Merryfield, VA: NOW, downloaded 30/09/2002

Costa, L. (1999), Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development: Conference Report, Chiang Mai: APWLD

Cox, R. (1999) 'Civil Society at the Turn of the Millennium: Prospects for an Alternative World Order', Review of International Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, pp.3-28

Dales, L. (2001) Identifying Feminists and Feminisms in 3 Kansai Women's Groups, GALE and EASH Joint Conference

Dore, R. (2000) Stock Market Capitalism: Welfare Capitalism: Japan and Germany versus the Anglo-Saxons, Oxford: Oxford University Press

English Discussion Society (1993) Japanese Women Now I, Kyoto: Shokado Publishers

English Discussion Society (1996) Japanese Women Now II, Kyoto: Shokado Publishers

Eto, M. (2001) 'Women's Leverage on Social Policymaking in Japan', PS, June 2001, pp.241-246

Falk, R. (1997b) 'Resisting 'Globalisation-from-above' Through 'Globalisation-from-Below'', New Political Economy, vol. 2, no. 1, pp.17-24

Foreign Press Center (2001) People in the News: Managing Director, NPO (Non-profit Organisation) Fifty-Net, Yuko Moriya, Japan Foreign Press Center, downloaded 06/02/2002

Fujieda, M. (1995) 'Japan's First Phase of Feminism' in Fujimura-Fanselow and Kameda (eds.) pp.323-341

Fujimura-Fanselow, K. and Kameda, A. (eds.) (1995) Japanese Women: New Feminist Perspectives on the Past, Present and Future, New York: The Feminist Press

Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office (2000) Policies implemented in FY(1999) to Promote the Formation of a Gender Equal Society, Tokyo, downloaded 06/02/2002

Hasegawa, H. and Hook, G. (1998) Japanese Business Management: restructuring for low growth and globalization, London: Routledge

Hashimoto, H. (2001) Men's Involvement in Gender Equality Movements in Japan, Women in Action, no.1, 2001, downloaded 24/11/2002

Hatch, W. and Yamamura, K. (1996) Asia in Japan's Embrace: Building a Regional Production Alliance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Iwao, S. (1993) The Japanese woman: Traditional image and changing reality, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Japan NGO Report Preparatory Committee (1999) Women 2000, Japan NGO Alternative Report, Japan NGO Report Preparatory Committee, downloaded 25/11/2002

Kaya, E. (1995) 'Mitsui Mariko: An Avowed Feminist Assemblywoman' in Fujimura-Fanselow and Kameda (eds.) pp.384-392

Keck, M.E. and Sikkink, K. (1998) Activists Beyond Borders, London: Cornell University Press

Khor, D. (1999) 'Organizing for Change: Women's Grassroots Activism in Japan', Feminist Studies, Fall 1999, vol. 25, no. 3, pp.633-661, downloaded 31/01/2002

Mackie, V. (1999) 'Dialogue, Distance and Difference: Feminism in Contemporary Japan', Women's Studies International Forum, vol. 22, no. 4, pp.599-615

Mann, M. (1997). 'Has Globalization Ended the Rise of the Nation-State'. Review of International Political Economy; vol.4, no.3, pp. 472-496

Mikanagi, Y. (2001) 'Women and Political Institutions in Japan', PS, June 2001, pp.211-212

Miura, M. (2001) 'Globalization and Reforms of Labor Markets Institutions: Japan and Major OECD Countries', Tokyo Institute of Social Science, Domestic Politics Project no. 4, July 2001, University of Tokyo

Moriki, K. (1997) 'Japanese Women Seek Solidarity with Asian Women' Osaka Dawn, Newsletter of the Dawn Center, (Osaka Prefectural Women's Center), Nov. 1997, pp.1-3

National Institute of Employment and Vocational Research (1988) Women Workers in Japan, NIEVR: Tokyo

Ogai, T. (2001) 'Japanese Women and Political Institutions: Why are women politically underrepresented?', PS, June 2001, pp.207-210

Passy, F. (2000) Socialization, recruitment and the structure-agency gap: A Specification of the Impact of Networks on Participation in Social Movements, Paper given 22-25 June 2000, Social Movement Analysis: The Network Perspective, Ross Priory, Loch Lomond, Scotland.

Shiozawa, M. and Hiroki, M. (1988) Discrimination against Women Workers in Japan, Tokyo: Asian Women Workers' Center

Sperling, V., Ferree, M. and Risman, B. (2001) 'Constructing Global Feminism: Transnational Advocacy Networks and Russian Women's Activism',Signs, vol. 26, no. 4, pp.1155-1185

Steinmo, S., Thelen, K. and Longstreth, F. (1992) Structuring Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Strange S. (1996) The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tanaka, K. (1995) 'The New Feminist Movement in Japan, 1970-1990' in Fujimura-Fanselow and Kameda (eds.) pp.343-352

Thelen, K. and Steinmo, S. (1992) 'Historical institutionalism in comparative politics' in Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth, pp.1-32

Tokyo Josei Union (1999), Tokyo Josei Union Newletter, Tokyo: Tokyo Josei Union

True, J. and Mintrom, M. (2001) 'Transnational Networks and Policy Diffusion: The Case of Gender Mainstreaming', International Studies Quarterly, vol. 45, pp. 25-57

United Nationals Development Programme (2000) 'Gender Empowerment Measure' in Monitoring Human Development: Enlarging People's Choices, downloaded 30/09/2002

Uno, S. (1997) 'What are Women's Centers in Japan?' Osaka Dawn: Newsletter of the Dawn Center (Osaka Prefectural Women's Center), Jan. 1997, pp.6-8

Usui, Y. (February 2002) Personal communication

Walby, S. (2000) 'Gender, globalisation and democracy', Gender and Development, vol. 8, no.1, pp.20-28

WINGS (2001) The catchphrase is "To have fifty percent of women in decision making!" Kyoto: Kyoto Wings, downloaded 06/02/2002

Working Women's International Network (2001b) 1999 Statement of Dr. Marsha Freeman, downloaded 01/02/2002

Worldwide Organisation of Women's Studies (2000) Women's Studies Association of Japan, downloaded 30/09/2002

Zenroren (1997) 'Final Report on Review of Labor Laws Published by Central Labor Standards Council', Zenroren newsletter, 1997, No. 75, Tokyo: Zenroren, downloaded 1/02/2002

Article copyright Beverley Bishop.