Play and Empowerment

The Role of Alternative Space in Social Movements

Volume 12, Issue 1 (article 4 in 2012). First published in ejcjs on 1 May 2012.

Abstract

Since the 1990s, social movements have emerged in Japan that stand out by their aspiration to reach out to and empower subaltern groups, such as freeters, NEET and social withdrawers. The article examines the role played by alternative spaces – spaces created within movements and designed to lack the oppressive features of mainstream society – in facilitating such empowerment. Such spaces face a variety of tasks – providing a refuge for subaltern groups, instilling hope that change is possible, and consolidating alternative space itself – which easily enter into conflict with each other. To examine how movements may relate to this difficulty, the article looks at three Japanese movements with NAM, New Start/New Start Kansai and the circle of activists around the Amateur Riot/Great Pauper Rebellion as central organizations or groups. Only the third successfully combines the three tasks, in large measure through its skilful use of the play-element. To understand how play can contribute to empowerment, I argue that we need to question definitions of play in terms of its separation from perceived social reality in favour of a definition of play as a pleasurable and mutual responding in relation to the social environment.

Keywords: alternative space, social movement, empowerment, play, Japan, precarity.

1. Introduction

Despite rising inequality and an increasingly precarious labour market since the bursting of its ‘bubble-economy’ in the early 1990s, Japan is often said to have produced little in the way of public protest, at least until 2003, when the upsurge of anti-war protests served to catalyze the precarity and ‘anti-poverty’ campaigns that quickly became a visible presence in ensuing years (Hayashi & McKnight 2005). A major argument of this paper is that the relative absence of such campaigns in the 1990s and early years of the new millennium should not be taken as a sign of inactivity among social movements. Instead it points to the inadequacy of approaching social movements through a narrow focus on their publicly visible dimensions.

While it is true that much discontent among young Japanese since the 1990s has been expressed through withdrawal rather than overt protest—drop-outs from school (futōkō), the withdrawal from the labour market of so-called nīto (NEET, ‘Not in Employment, Education, or Training’), or from social life as such by social withdrawers (hikikomori)—important reorientations have also taken place among social movements in the same period. As Mōri (2005, 2009) points out, many trends among today’s movements were prepared already in the 1990s, when activists started to dissociate themselves from established Leftist organizations by trying out new forms of ‘cultural’ activism and looser and less hierarchical forms of organization. Many of those activists were young women and men without regular employment—so called freeters—who in the absence of social safety nets were living a precarious life near or below the poverty line. A conspicuous trait among many new movements that have developed since the 1990s has been their attempt to reach out to groups that are marginalized or excluded from important arenas of society—including freeters, the homeless, foreign workers, NEET, social withdrawers and the mentally ill (Cassegard 2012). I will refer to these groups as subaltern in order to emphasize that they share an experienced inability to participate fully in society or to make themselves heard effectively in the mainstream public sphere.

The aim of this article is to study how social movements have attempted to empower these groups and what role alternative space has played in the process of empowerment. By empowerment I mean the strengthening of people’s self-confidence as political actors. It thus implies what Drury & Reicher (2005:35) describe as the “confidence in one’s ability to challenge existing relations of domination.” Empowerment occurs when people regain the sense that their actions and opinions matter and that they have the power to influence things in society which they deem to be important. Studying social movements from the perspective of empowerment implies relativizing the presuppositions that movements operate above all through protests and other public manifestations, and that their activities are played out above all in the mainstream public sphere. While public protests are the outwardly most visible aspect of social movement activism, a usually less visible but fully as important function of movements that attempt to reach out to subalterns is to provide alternative spaces where the sense of powerlessness may be counteracted.

By alternative space I mean spaces that are felt by subalterns to offer a sanctuary or relief from the oppressive features of mainstream arenas. They are thus spaces that are normally located outside the mainstream public. Negative value judgments on subalternity are suspended and efforts are made to ensure an environment that is more responsive to the needs and wishes of participants than mainstream society. Unlike so-called ‘safe spaces’ (Gamson 1996), they are not necessarily spaces of withdrawal that must be protected from outside society. What is crucial is that they are not felt to induce a sense of powerlessness. Alternative spaces can thus be created in public, in moments when mainstream society is felt to shed at least part of its oppressive features. This means that they are not necessarily tied to any particular place. Although they usually need distance from the mainstream public in order to thrive, the distance can be closed. In fact, it is often a sign of successful empowerment that subaltern groups return to the mainstream areas of society and manage to at least temporarily experience them as liberated or non-oppressive space.

The overall thrust of this article is as follows. I start by arguing that the alternative spaces set up by social movements play an important role in furthering empowerment since they provide a crucial mediating link between the public sphere and spaces of withdrawal of subalterns. However, this mediation involves them in a precarious balance between three requirements: working for social change, providing arenas for the participation of subalterns, and consolidating the spaces themselves. These requirements, I suggest, can only be met if alternative space provides opportunities for what I call abstract as well as concrete modes of interaction. An important source of tension or conflict lies in the need for alternative space to alternate between these modes. A fruitful vantage-point on social movements, I argue, is to look at how they have handled this tension and to what extent they have managed to avoid or mitigate it.

To illustrate my concepts I next turn to three cases, representing social movement groups that in recent years have engaged in building alternative space in Japan: 1) the New Associationist Movement, an organization that in 2000-2003 devoted much of its energy to establishing an alternative economy; 2) New Start and New Start Kansai, two organizations engaged in the support of social withdrawers and NEET; and 3) the activists around the Amateur Riot and the Great Pauper Rebellion, well-known in recent years for festive and boisterous street parties through which they attempt to reoccupy space from mainstream society. Each instance has given different emphasis to the above-mentioned three requirements: one prioritizing the construction of a particular type of alternative arena, another focusing on providing arenas for subalterns, and a third engaging in playful forms of public protest.

Finally, taking my cue from the discussion of the Amateur Riot and the Great Pauper Rebellion, I argue that the creation of alternative spaces conducive to empowerment can be facilitated by play. Play is important for empowerment since it mitigates the tension between abstract and concrete modes of interaction, providing relief to the subaltern from the pressures of mainstream society and helping them regain a sense of agency. Play, I argue, should not be understood as necessarily separated from reality, but as the opposite of powerlessness. It can thus mean playing with reality, something which I suggest occurs in particularly empowering moments in street parties and demonstrations.

2. Social movements and the functions of alternative space

What did I mean by stating that social movements, in order to aspire to the empowerment of subaltern groups, cannot be active solely in the public sphere? The ‘public sphere’ is a dimension of social life where citizens can deliberate on their common affairs while disregarding matters and circumstances deemed to be of only ‘private’ relevance (Habermas 1989; for a discussion, see Cassegard 2011). Although central to the functioning of modern democracies, it is also a stratified arena which throughout its history has relegated the voices of groups such as women, the lower classes, foreigners, minorities, children and slaves to the margins or excluded them altogether (for an overview of criticism against the ‘public sphere’, see Dahlberg 2003).

As Nancy Fraser (1992) points out, numerous subaltern groups have managed to raise their status by temporally or partially exiting the mainstream public sphere in order to form their own ‘subaltern counterpublics’—discursive arenas where they are able to find refuge from and challenge the exclusionary norms of the surrounding society. As a first step in their empowerment, such groups may need sheltered spaces where their stigmatisation can be shared, exposed and discussed without fear of discrimination. However, the ‘counterpublics’ never remain mere enclaves. Ultimately, they return to the mainstream public and ‘help expand discursive space’ by bringing stigmatisation out into the open, protesting against discrimination and insisting on their right to public visibility. The counterpublics therefore possess a ‘dual character’: ‘On the one hand, they function as spaces of withdrawal and regroupment; on the other hand, they also function as bases and training grounds for agitational activities directed toward wider publics’ (Fraser 1992:124).

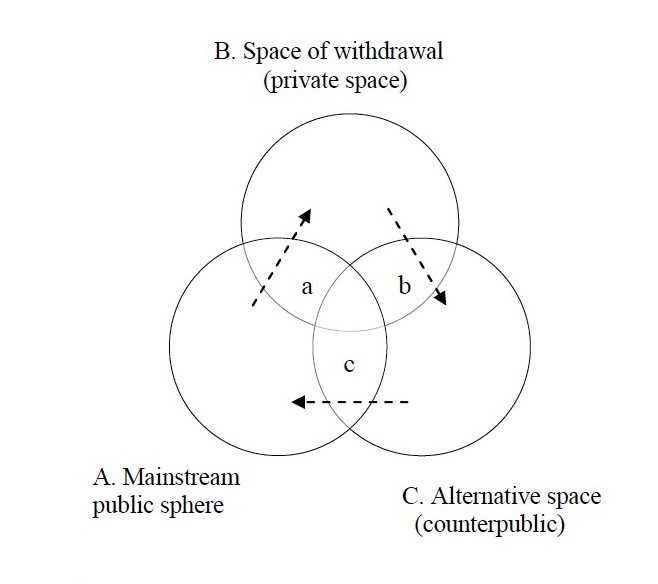

Figure 1 clarifies this dual orientation. Social movements that aspire to empowering subaltern groups cannot confine themselves to operating within the mainstream public sphere (A). Instead they need to establish a counterpublic or alternative space (C), which is open to the participation of subaltern groups (B). The arrows in the figure are meant give a sense of the movement suggested by Fraser: the subaltern are people who have withdrawn (a) from the mainstream public because of experiences of exclusion or inability to participate meaningfully. Their road to recovery needs to start by regroupment (b) in alternative space, before reaching the stage of public protest or other activities aiming at social change (c). Withdrawal (a) can be experienced as a disempowerment, the latter two processes (b and c) are successive stages of empowerment. The activities of social movements, then, are not exhausted in challenges and confrontations directed at the ills of surrounding society. The more people react to setbacks and frustrations by withdrawing into a world of experienced powerlessness, the more movements need engage in setting up alternative space in order to address the task of the empowerment of such groups.

Figure 1.

The figure suggests that there are three important tasks for movements engaging in empowerment. The first is to provide a refuge for subordinated people where they are no longer subordinated, welcoming them to a sheltered ‘safe’ space which also offers an alternative to the forced or self-chosen confinement in a purely private life. The second is the strengthening and consolidation of the alternative spaces themselves (for instance by building up trust, contacts and skills, providing services to participants, or experimenting with participatory democracy, alternative currencies, or ecological agriculture). A third task is to make people feel, through participation in action itself, that they have the power to protest and work for meaningful changes in society and their own lives.

A fruitful vantage point on social movements is to look at how they relate to these tasks. The reason is that tensions can arise between them. The question of how movements have handled shifts between the tasks and possible tensions between them has seldom been treated in previous research. Fraser never problematizes how subaltern counterpublics shift between ‘spaces of withdrawal and regroupment’ and ‘bases and training grounds for agitational activities’. The same goes for much of the research devoted to ‘counterpublics’ or ‘alternative publics’. In the literature on ‘free’, ‘safe’ or ‘unpatrolled’ spaces, one strand of research focuses on the strategic benefits of such space for oppositional movements or dissidents, but gives little consideration to the function of such spaces as shelters for people who are oppressed but not yet empowered enough to want to be oppositional (Scott 1990, Tilly 2000). Another strand emphasizes the importance of ‘free’ or ‘safe’ spaces as shelters, but tends to downplay their role as the basis for public protest (Gamson 1996). Even scholars who pay attention to both of these functions and to conflicts that may accompany shifts between them tend to focus on factors internal to the ‘free space’, viewing empowerment as having little to do with what happens when activists venture outside the movement network to interact with mainstream society (Evans & Boyte 1992, Polletta 1999).

The possibility of conflicts between the tasks of public protest and of reaching out to the subaltern has been particularly acute among social movements that have addressed the empowerment of subalterns in Japan—partly because of the severity of the withdrawal among some groups, which has often meant that they have given up hope in using voice and political protest (Toivonen et al 2011), and partly because of the lingering negative image of political activism in Japan, a legacy of the perceived failure and defeat of the so-called New Left in the 1970s (Igarashi 2007:120). These factors have contributed to a reluctance among younger generations to engage in activism, but also to a tension between subalterns and activists in alternative spaces established by movements in Japan.

A recurring source of tension has been that opening up space that can serve as shelters for the subaltern has often required abstract forms of interaction, while protesting or working for social change require concrete ones. By abstraction I mean the process whereby one systematically brackets one or several aspects of the given social reality, while concretion stands for the process whereby such aspects are attended to and allowed to guide interaction. Simmel’s (1997) discussion of the sociability of bourgeois salons is a good illustration of bracketing. The interaction here is playful since participants engage in interaction for its own sake, while disregarding the material interests or personal problems that burden it in everyday life. Such interaction has a ‘democratic’ character since all participants, within certain boundaries, behave as if they were equal. In that way, they create an artificial environment in relation to which individuals no longer appear powerless or ‘negligible’. A sensation of pleasurable lightness is created through a bracketing of social reality. However, Simmel’s discussion also demonstrates the limits to how far abstract interaction can contribute to empowerment. The ‘democratic’ semblance is fragile since the ‘realities’ of social life are never wholly forgotten even in salons (Simmel 1999:124f). At most this playful form of interaction offers a partial and temporary refuge. Even more problematically, while bracketing creates a democratic semblance, it also prevents real inequalities in power, wealth and status from being challenged.

An antidote to the feeling of powerlessness seems to require some form of acting back on the surrounding society, and this engagement in turn requires concretion, i.e. giving attention to aspects previously bracketed. However, the turn towards concretion is a risky process. If it occurs too abruptly there is a risk of alienating those who sought refuge in alternative space from the experience of marginalization. New exclusions, this time from alternative space itself, can occur if activities revive painful memories, bring about renewed setbacks, or create new hierarchies. This element of ‘heaviness’ can appear even in activities that are superficially playful, like street parties or free concerts. To manifest an alternative life in public means that participants have to expose themselves to stigmatizing or disapproving gazes from onlookers, which can no longer be abstracted away.

If abstraction is necessary to create spaces where subalterns can participate on an equal footing with others, concretion is just as necessary to bring about social change. The difficulty is how to combine them. A movement that overemphasizes activism and confrontation risks alienating the subalterns, while one that rests satisfied with providing an arena for abstract interaction will be unlikely to cure the participating subalterns’ sense of powerlessness. If too much energy is devoted to providing an abstract place in order to remove the ‘thorns’ of reality and facilitate people’s recovery, the aspiration to bring about social change risks being pushed into the background. If instead the task of confronting the surrounding society is overly emphasized, subalterns risk having to face these thorns again. To illustrate how movements or networks of movements can relate to this difficulty, I will turn to three Japanese movements that in recent years have addressed the problems of subaltern groups.

3. NAM—The New Associationist Movement

One of the first groups to explicitly criticize ‘globalization’ in Japan was NAM (New Associationist Movement). It was established in 2000 by Karatani Kōjin, one of Japan’s most well-known intellectuals, with the aim of ‘resisting capital, nation and state’ (for its program and theory, see Karatani 2000, 2003). It quickly established a series of local chapters and around 600 members, but was dissolved only three years later. Despite its brief existence, it is interesting for two reasons. Firstly, it illustrates the importance of the negative legacy of the New Left—symbolized in popular consciousness by infighting and by the violent end of the Japanese United Red Army—as one of the major hurdles for radical activism to develop in Japan in the 1990s. Karatani’s explicit ambition with NAM was to grapple with this legacy by working through and renovating the organization and methods of the radical protest movements. In particular he rejected the violent riots and the street fighting that in his view had characterized the classical bourgeois revolutions as well as the student unrest of the 1960s. What mattered was instead to break out of the sterile cycle of ‘romantic’ protest and defeat which had characterized Japanese social movements until now (Karatani 2005, Cassegard 2008).

Secondly, NAM stands out through the high hopes it invested in the idea of building alternative space outside the mainstream public. According to Karatani, efficacious resistance does not consist in rebelling against or confronting the system, but in abandoning it and building alternatives. From the very start NAM was presented as the seed of a future society that would gradually replace the established capitalist system. In particular he put hope in the peaceful growth of non-capitalist economies that would also function as safety nets for activists and marginalized groups. The aim of social change was thus present in NAM, but was never regarded as requiring any direct or overt confrontation with the surrounding society. Instead priority was put on establishing and expanding arenas for alternative living.

NAM also tried to reach out to subaltern groups. This ambition was evident in the project of establishing an alternative school for school refusers (the Osaka New School, which was established as a Non-Profit Organization in 2001) where teachers would be volunteers who would be paid in an electronic currency named Q (Yamazumi 2001). It was also manifested in the Q-project itself. Q was conceived as an Internet-based LETS (Local Economic Trading System), in which capital accumulation would be meaningless since the currency could be freely issued at the time of an exchange (the price is subtracted from the buyer’s individual account and deficits represent his or her debt to the LETS-community). According to Karatani, people were welcome to participate in the Q-project out of self-interest, without sharing any common movement goal, since what mattered was not the inner motive for participation but the coming into being of an alternative system with the potential of undermining and replacing capitalism. The advantage of the system was that it was ‘impersonal’ and, like capitalist markets, allowed for interaction between strangers. This impersonality and openness distinguished it from small-scale gift economies from which outsiders are excluded. NAM itself was conceived by Karatani as an open and impersonal association modelled on what he called ‘transcritical space’, i.e. a space lying in-between or outside communities, and therefore never becoming closed or dominated by any single norm-system (Karatani 2003). Such an abstract arena would, he hoped, facilitate the participation of groups disillusioned with existing forms of political activism. In contrast to the stress on solidarity and identity in most social movements, NAM was thus consciously designed to be a forum for abstract interaction that would be efficacious without any common identity among its participants. The very fact that an increasing number of people participated in NAM and its alternative economy would be sufficient to change society. Karatani compares this to ‘brain-drain’. ‘When gifted people start pouring into non-capitalist forms of production, capital is in for trouble’ (Karatani & Murakami 2001:77).

How did NAM manage the balance between abstraction and concretion? Effort was above all put into creating abstract forms of interaction in which the ‘personal’ was superfluous. This abstraction never appears to have been characterized by the playfulness or ‘interaction for its own sake’ described by Simmel. What mattered was instead to subordinate interaction to an overarching goal already defined by Karatani in the NAM’s principles, namely the creation of space for a life beyond ‘capital, state and nation’. In this way, NAM poured its greatest energy into the development of alternative space itself, and in particular the project of an alternative economy. In contrast, no weight at all was put on public confrontations and protests and only relatively little on the participation of subaltern groups. Since it at the same time isolated itself from other movements it tended to become a closed organization whose relations to the wider public as well as to subalterns were weak. As a result of its rejection of public protest, NAM appears to have lost part of the attraction that protest movements exert. Thus Suga Hidemi defended the street protests of the 1960s against Karatani’s criticism by referring to the sense of ‘fun’ and human contact which they created, and questioned the viability of movements lacking such elements (Karatani & Suga 2005:204f). As for the participation of subalterns, the alternative school was never given the same high priority as the Q-project, which was central to NAM. The ambition of reaching out to subalterns was also stymied by NAM’s conscious elitism. When NAM was founded, Karatani turned above all to academics, intellectuals and artists, while political activists were avoided. NAM, he claimed, was a ‘university’ that would be an alternative platform for the education and training of intellectuals. The result appears to have been mixed: even if some members talk appreciatively about the meetings and contacts that the discussions brought with them, NAM soon became criticized for being top-heavy and the discussions far from free. When the Q-project faltered internal conflicts were triggered that led to NAM’s dissolution. Many of the members instead became engaged in other activities, such as the emerging precarity movement, alternative agriculture, or support to social withdrawers.

4. The sibling organizations New Start and New Start Kansai

I now turn to a network centred on two sibling organizations—New Start in Chiba and New Start Kansai in Tonda outside Osaka (established in 1993 and 1998 respectively). Both have as their primary aim the provision of help and support to social withdrawers (hikikomori) and NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training), i.e. young people who have withdrawn from participation in social life or the labour market. Support groups became popular during the 1990s and exist in a wide variety of forms, some harshly authoritarian and others—such as New Start and New Start Kansai—being more accepting and accommodating (Furlong 2008:317f, Toivonen & Miller 2010). Common to the more accommodating support groups is that they try to provide alternative space, where withdrawn young people can practice human interaction while recovering and find shelter from the pressures of mainstream society. As the sociologist Higuchi Akihiro states, an important task for these spaces is to give ‘respite’ to the withdrawers. Rather than hunting them back to a cold competitive and exclusive society by education or training programs, they need time to sort out their thoughts and are better served by social activities, art, or working in Non Profit-Organizations building up local welfare (Higuchi 2005:10f).

Compared to other support organizations in Japan, New Start and New Start Kansai stand out by their relatively radical vision of an alternative society where the demands for efficiency, profit and growth are downplayed. Such a society would be ‘communist’ in the sense that each would contribute according to ability and receive according to need, and which is close to the ‘slow life’ ideal advocated by Tsuji Shin’ichi (Futagami 2005, Tsuji 2001). The ultimate aim of support activism is in other words not the re-adaption of subalterns to the existing society, but to work for a better society were the mechanisms of exclusion are no longer in force. The two organizations also strongly emphasize that the problems of withdrawers cannot be solved within the family alone and that what matters is the creation of new social ties and a circle of friends outside the family (see Futagami 2005, 2006; Nakajima 2007 for presentations of the movement’s program).

Neither of the two organizations engages in open confrontations (although there are examples of social withdrawers in these organizations who have become activists on an individual basis; cf. Ueyama 2001, interview with ‘K’, support worker in New Start, 2007-08-07). Instead both engage forcefully in the construction and expansion of alternative space. In the case of New Start one can see a close cooperation with local authorities. Apart from its extensive facilities in Chiba, New Start has established a number of ‘mixed welfare villages’ with the help of authorities where it is hoped that social withdrawers, elderly and disabled will engage in mutual help and young people be given work experience and opportunities to earn their own money (Futagami 2005, 2006; Sawaji 2007).

New Start Kansai has chosen a partially different way to create alternative space. The organization is more small-scale and negative to cooperation with authorities (interviews with New Start Kansai’s representative Nakajima Akira 2007-07-18, and ‘E’, member of Workers Collective Support Centre 2007-07-06). Lacking the resources of its sibling organization in Chiba, it has instead poured its efforts into setting up a complex cooperative network with other organizations in the Kansai area, several of which have been established by New Start Kansai itself. First, there is the Non-Profit Organization (NPO) Slow Work, which was founded in 2002 (under the name New Start Workers) and works in close symbiosis with New Start Kansai. While the latter concentrates on the daily running of support activities, the former focuses on events and publications propagating an ‘alternative form of work’. In 2002 the Workers Collective Support Centre was established to support the creation of worker collectives among the staff as well as among the young people given work experience in the cafés and shops of the network. Through this organization, New Start Kansai also took part in the founding of two networks for alternative currencies, Kyoto LETS (2001) and Osaka LETS (2002) in order to try out the idea that participating in such economic systems would help social withdrawers discover a way back to social life (Ueyama 2000). In this network, alternative cafés also play a conspicuous role. Most well known is Café Commons, established by Slow Work in 2005, an ecologically oriented café staffed mostly by young inmates that also functions as an event space for concerts, LETS markets, study circles, talks with invited activists and academics, and other activities.

One effect of creating this network has been the establishment of a system of interlinked alternative spaces with varying degrees of public visibility. The network thus provides not only shelters, but also pathways that young people receiving support can flexibly try out in order to find activities that suit their present needs. The possibility of travelling through the network gives them the possibility of sometimes opting for more abstract and sometimes more concrete forms of interaction, and thus to regulate their process of recovery.

However, the fact remains that interaction in the network is to a large extent structured by the division between those who provide and those who receive support—something that prevents the establishment of a completely abstract space in which all traces of subalternity are bracketed. The differentiation between activists and subalterns is further accentuated by the fact that the former uphold a political vision of an alternative ‘form of work’ to which, as the activists themselves state, the youngsters receiving support are only receptive to a limited extent. To be sure, as the withdrawers recover, they become increasingly capable of turning the gaze to their own situation and verbalizing it, but this ability rarely turns them into activists. What in practice counts as a successful recovery is usually that they feel able to start looking for work or to study, i.e. that they return to society in its present state rather than trying to change it by challenging the mechanisms that produced their previous experiences of exclusion. There is in other words a gap between the movement’s vision about an alternative society and its more direct goal of contributing to the recovery of the subaltern (the gap between older Left activists and young social withdrawers is discussed in Ueyama 2001, and in several interviews with activists, e.g. ‘E’ 2007-07-06, ‘K’ 2007-08-07).

Among the three tasks of alternative space, New Start and New Start Kansai place the greatest emphasis on the support to subalterns but also promote the construction of arenas for an alternative life. To both organizations these two tasks are closely interrelated. Both actively encourage the empowerment of subalterns by letting them spend time in the network, providing places for them to be, to eat or sleep or meet others in the same situation and making it possible for them to engage in volunteer work and creative activities, to participate in alternative economies, and to interact with outsiders and strangers in places like cafés. In both organizations there is an expectation that the existence of the network will facilitate flexible shifts between levels of engagement, in pace with the recovery of power and self-confidence among the young people they try to support.

4. The Amateur Riot and the precarity movement

Since 2004 the streets of Tokyo and other big cities in Japan have offered the sight of a new kind of May Day demonstrations: street parties, colourful events with dancing demonstrators that in slow pace follow a truck pumping out music over the streets. The demonstrators are largely freeters but there is also a notable element of older day labourers, homeless and NEET. They call themselves the ‘precariat’, a term by which they try to capture the entire stratum of workers with insecure or precarious living conditions that has grown in pace with the deregulation of the labour market that has accelerated in Japan since the mid-1990s.

The precarity movement’s protests target not only the deregulation, but also the tendency to put the blame for the precarious living condition of young people on their own laziness or unwillingness to lead a conventional life. Apart from its street demonstrations, the movement also works for change through negotiations with employers and information campaigns. The success of the movement can be seen in the popularity of its demonstrations, in the proliferation of new unions and Non-Profit Organizations dealing with the problems of the new flexible labour power, in the establishment in 2007 of a nationwide network which has enabled coordinated actions on a larger scale than before, and in the impact the movement has achieved in public with its interpretation of reality. One can also see clear responses from the establishment: Diet members have participated in the demonstrations, courts have handed down sentences ordering companies to pay fines or stop operations, and since 2007 the government has been promising reforms to stem problems caused by the deregulation of the labour market.

The precarity movement has also partly succeeded in its effort to encourage subalterns to participate in public manifestations. Prominent members of the General Freeter Union in Tokyo are publicly known as former social withdrawers (Ichino 2009). In Fukuoka, the Freeter Union Fukuoka has been particularly successful in mobilizing NEET and social withdrawers, and helped arrange the first NEET-demonstration in Japan in Kumamoto in 2008 (Umano 2008).

What is it in the precarity movement that encourages the participation of subaltern groups, and gives them confidence to protest? As shown in Cassegard (2012), the importance of verbalization forms a common thread in most accounts of empowerment among participants in the precarity movement, either in the form of sharing experiences with others within alternative space or directing one’s voice outwards, to the general public. A second important element is action itself, along with the realization that one is not powerless to act back on society. As many activists state, participating in demonstrations has led them to the ‘discovery of a new self’, a self which is no longer a passive victim but an active agent. The festive or carnivalesque character of street parties also appears to play an important role to at least some groups that feel alienated from more traditional forms of political activism. As Umano (2008) points out the wish to act out and let go of their restraints is often what attracts social withdrawers and NEET to street parties.

What is the role of alternative space in this movement? Here I would suggest that we can see a long-term shift. Much of today’s activism traces its roots to developments in the 1990s. One of the groups that served as a predecessor of today’s precarity activism was the League of good-for-nothings (Dameren, founded in 1992), which played a pioneering role in the development of alternative places where activists and subalterns could associate (Mōri 2005, Cassegard 2012). Many social withdrawers and mentally ill participated in the league, attracted by the term ‘good-for-nothing’ in which they recognized themselves. The main activities were talking and associating. Irreverent humour played a conspicuous role (Kaminaga 1999, Kyūkyoku 2006). Although seldom engaging in visible public protest, the group fulfilled a latent political function as a laboratory for trying out new lifestyles and as a sanctuary where marginal groups could recover, protected from sanctions by the outside world.

Among the most well known groups that today carry on the league’s legacy are the activists of the Amateur Riot (Shirōto no ran) and the Great Pauper Rebellion (Bimbōnin daihanran), who are based in an arcade near Kōenji Station in Tokyo where they run a number of recycle shops, a free space and a café. In these groups physical place plays a great role because of the activists’ effort to create a low-cost environment in the arcade for freeters and other ‘paupers’, but also because they consistently use the street as a scene for humoristic and at times wild pranks reminiscent of artistic happenings. More than as a mere sanctuary, alternative space is here seen as something with the potential to spread to and ‘infect’ the surrounding society. Making fun of the police and other authorities is a recurring theme in their activities, which include cooking nabe (pot dishes) on the pavement outside the fashionable Roppongi Hills skyscraper, tricking the police to guard ‘skipped demonstrations’ where no activists show up, or using legal loopholes to carry out unconventional activities such as turning election campaigning into street parties. As Matsumoto Hajime, founder of the first recycle shop, says, the activities aim to create a ‘post-revolutionary world in advance’ and to demonstrate to everyone how fun it is (for accounts of these events, see Amamiya 2007:226-238, Matsumoto 2008a, 2008b:95-138). Mixed in with the daily work in the shops and the pranks are also demonstrations with serious themes, such as the ‘Great Anti-Nuclear Rock Festival Demo in Kōenji’ which was arranged by Matsumoto and other activists in April 2011, in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear accident, and attracted an unprecedented number of participants.

Compared to NAM, New Start and New Start Kansai, the precarity movement has put a much stronger emphasis on public protest, but some groups—building on the legacy of the League of good-for-nothings—also make efforts to build up arenas for alternative living and encourage the participation of subalterns. What has enabled them to combine these three tasks so relatively successfully? A clue is provided by the role of play. As the activities of groups like the Amateur Riot and the Great Pauper Rebellion show, play is not necessarily confined to spaces like the salons described by Simmel that are segregated from social ‘realities’. Instead, play is brought out on the street and confrontation itself assumes the character of play. But how is that possible? The answer, I suggest, lies in how play facilitates the reconciliation of abstraction and concretion.

5. The significance of play for empowerment

So far I have mentioned play above all in connection with abstract forms of interaction, such as the sociability Simmel observes in bourgeois salons. The idea that play presupposes an abstraction from social realities is in line with the common definition of play as an activity isolated from what participants experience as ‘reality’. Thus Huizinga (1955:7f) sees play as a voluntary ‘leave-taking from “real” life’. To Groos (1898: 301, 304), it is a ‘conscious self-deception’ accompanied by the knowledge that the situation is not real, and Caillois (2001:158f) describes it as a ‘refuge in which one is master over one’s fate’ and which is possible by virtue of its ‘separation from reality’. To these thinkers the sphere of play is almost by definition a fragile construction that easily collapses through the contact with the outside world. This conception of play needs to be questioned, because if we consent to it will become hard or impossible to understand how the precarity movement manages to transpose the play form to the street. If play can only unfold in separation from social reality, how then can it be that it not only survives, but even seems to thrive in the confrontation with this reality? This question is related to the following one: should what we are seeing in the playful confrontations enacted in the precarity movement’s street parties be classified as abstract or concrete interaction? When demonstrators denounce neoliberal deregulations or work place abuses while at the same time proclaiming themselves to be ‘good-for-nothings’ or adopting names like the ‘precariat’, then this appears to have very little to do with abstract interaction or any bracketing of given social categories—but neither can it be described as a concrete interaction in which participants are re-embedded in these categories.

Recall that concretion and abstraction have been defined in terms of paying attention to or bracketing aspects of a given social reality. A possibility of relativizing the opposition between them exists if this reality loses its semblance of fixity and stability, which is exactly what occurs in moments when people that they have the power to change it. In a changeable environment every statement about reality easily turns ambiguous. It is in this light that Rancière’s claim should be understood that politics is essentially about ‘improper’ names and ‘misnomers’ (Rancière 1999). When the subalterns make themselves visible in public they often do so through a rejection of given identities in favour of new categories that change the field. It is this process that Rancière calls ‘subjectivation’ and counterposes to ‘identification’, the delimitation of a group to a given unambiguous category. An example of such subjectivation is when demonstrators refer to themselves as ‘precariat’, ‘good-for-nothings’ or ‘paupers’—all labels that seem to balance between the serious and the playful. As Rancière points out there is something paradoxical about such names, which despite seemingly denoting a fixed entity at the same lack natural borders and—in line with the principle that everybody polemically assumes the name of the most discriminated—seem able to include almost anyone.

What Rancière calls politics, a subaltern group’s visibilisation of itself in public, thus creates the possibility of circumventing the opposition of abstraction and concretion. I have already stated that certain forms of abstract interaction can facilitate the empowerment of marginal groups by offering them shelter from the yardsticks of mainstream society, but we can now add that such a shelter is also provided everywhere that the feeling gains ground that the days of these yardsticks are themselves numbered. This creates new possibilities for the participation of subalterns in society. As a matter of fact, the opposition between abstraction and concretion is not symmetric, because what abstraction brackets is always a given reality, while the reality encountered by movements is one which they are trying to change. The social reality that participants in movements encounter is therefore not the same as the one from which they once may have tried to distance themselves. Even if the subalterns again turn they eyes to and thematize their situation in society, this time it is not to identify with their roles but to question or reject them.

The question of how play is possible in the confrontation with society can now be answered. The return to society, when it occurs with the intention of changing it, can create forms of interaction just as light, playful and free from the seriousness of daily life as those that can be produced by abstraction. Accounts of revolts and riots often mention such feelings of lightness. ‘It was a feast without beginning and without end’, Bakunin (1977:56) writes about the February Revolution in 1848, and the Situationists similarly described the experience of revolt as ‘an all-embracing reinserting of things into play’ (Vaneigem 2001: 264).

A conclusion can now be drawn about what play is. Play is not the opposite of reality, as is often asserted, but the opposite of powerlessness. Play arises when the feeling of powerlessness is overcome. In salons and cafés this can occur because we bracket our roles and statuses in the surrounding society and focus solely on the relations with other people sharing the same arena. As Simmel points out, the effect of bracketing is to create a separate sphere of activity in which participants are no longer subject to the necessities of the outer world. In order to understand how this outside world itself can be ‘reinserted into play’ we need to accept that what gives birth to play is not necessarily the distance to the necessities of reality, but rather the softening or disappearance of the feeling of necessity as such. What is characteristic of play is not that people create a world that is only ‘in pretence’, but that they are able to act with a feeling of pleasure in whatever social world they happen to be oriented towards for the moment. This in turn presupposes that this world ‘responds’, that they are able to influence it and bring about responses through their actions. A clue to how the wider society can be transformed into a playful arena is provided by Asplund, who points to responsiveness as the very source of the feeling of ‘fun’ that characterizes play. When he writes that ‘in play the responses of the participants decide over the world instead of the other way round’ (1987:67), this can at first sight appear to resemble Simmel’s description of sociability as interaction for its own sake, but in actual fact Asplund opens up for a quite different way of grasping play. The reason is that defining play as responsiveness makes it possible to assume that play can exist even in the wider society outside the salons, provided that this society does not refuse to respond.

6. Concluding words

When sociology has treated the question of what experiences characterize modern society it has often pointed to the individual’s sense of powerlessness and inability of making its voice heard against the overpowering machinery of society. In this article, I have argued that social movements can counteract this sense of powerlessness through the construction of what I call alternative space. To contribute to empowerment, such spaces need to be able to provide ‘shelters’ to the subaltern from the pressures of mainstream society but they also need to consolidate themselves and to be bases for social change. In Japan, social movements since the 1990s have grappled in varying ways with how to combine these requirements. In the 1990s, new directions in social movement activism became visible among activists who were dissatisfied with the organizations of the New Left, which were perceived as ineffectual and unresponsive to the needs of the subaltern. In groups such as the League of good-for-nothings or NAM, attempts were made to overcome the limitations of the New Left by consciously experimenting with the construction of alternative spaces to which subalterns were welcomed. Providing places for the recovery of the subaltern has also been the strategy of New Start and New Kansai. All of these groups have had social change as an underlying goal or ideal, but none of them have made use of visible public protest in order to reach that goal. NAM’s projects never really took off the ground. In the case of New Start and New Start Kansai, recoveries on the individual level are disconnected to the overall vision of social change. Since the cause of exclusion is diagnosed to lie in society, the fact that individual recoveries occur can only be regarded as a partial success. In the case of the League, a partial success of another kind can be observed. Here a line of continuity exists to present-day groups in the precarity movement, in which protest-oriented activism is revived even as the attempts to create alternative spaces and to empower the subaltern are retained. As I have suggested, there is good reason for this development, since the realization among participants that they are capable of exerting pressure on society may well be crucial in furthering their sense of empowerment.

As the case of the Amateur Riot and the Great Pauper Rebellion shows, play is an important element that may have facilitated for precarity activists to set up alternative spaces that work both as refuges for subaltern and as bases for protest. Play helps alternative space shift smoothly between its various tasks by downplaying the conflict between abstraction and concretion. This is because it counteracts the sense of powerlessness against the things included in the play. As Simmel shows, play helps create a ‘light’, abstract mode of interaction for people who need a shelter or refuge from mainstream society. Acknowledging the significance of such shelters makes it easier to see that the public protest is not the only or not necessarily even the most central activity of social movements. Play, however, is not limited to sequestered, abstract spaces. The range of things included in play can be expanded, even to the point where—as the Situationists suggest—the world as a whole becomes ‘re-inserted into play’. What we see in the street parties and demonstrations of the precarity movement is least tendentially that a playful attitude at spreads out into public space and shapes the relation to outside society. Such moments, I have argued, are necessary for empowerment since they offer subaltern groups the chance of experiencing that they are not one-sidedly subject to the power of society, but are also capable of ‘retaliating’ by acting back on it and experiencing it as changeable through human action.

References

Amamiya, Karin. 2007. Ikisasero! Nanminka suru wakamonotachi. Tokyo: Ōta shuppan.

Asplund, Johan. 1987. Det sociala livets elementära former. Göteborg: Korpen.

Bakunin, Mikhail. 1977. The Confession of Bakunin. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Caillois, Roger. 2001. Man and the Sacred. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Cassegård, Carl. 2008. “From Withdrawal to Resistance: The Rhetoric of Exit from Yoshimoto Takaaki to Karatani Kojin.” Japan Focus: The Asia-Pacific Journal, March 4, http://japanfocus.org/products/details/2684.

———, 2011. “Public Space in Recent Japanese Political Thought and Activism: From the Rivers and Lakes to Miyashita Park.” Japanese Studies 31(3):405-422.

———, 2012. “Let us live! Empowerment and the Rhetoric of Life in the Japanese Precarity Movement.” positions: east asia cultures critique (forthcoming).

Dahlberg, Lincoln. 2003. “The Habermasian Public Sphere: Taking Difference Seriously?” Theory and Society 34: 111-136.

Drury, John & Reicher, Steve. 2005. “Explaining Enduring Empowerment: A Comparative Study of Collective Action and Psychological Outcomes.” European Journal of Social Psychology 35: 35-58.

Evans, Sara M. & Boyte, Harry C. 1992. Free Spaces: The Sources of Democratic Change in America. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Fraser, Nancy. 1992. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy”, in Craig Calhoun, ed., Habermas and the Public Sphere. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, pp. 109-42.

Furlong, Andy. 2008. “The Japanese Hikikomori Phenomenon: Acute Social Withdrawal among Young People.” The Sociological Review 56(2): 309-325.

Futagami, Nōki. 2005. Kibō no nīto: Genba kara no messēji. Tokyo: Tōyō keizai shinō-sha.

———, 2006. “The ‘Integrated Community’: Toward the Transformation of the Hikikomori Archipelago Japan.” Japan Focus, October, http://japanfocus.org/-Futagami-Nouki/2239 (2010-07-05).

Gamson, William A. 1996. “Safe Spaces and Social Movements.” Perspectives on Social Problems 8: 27-38.

Gaventa, John. 1980. Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Genda, Yūki. 2005a. A Nagging Sense of Job Insecurity: The New Reality Facing Japanese Youth. Tokyo: LTCB International Library Trust, International House of Japan.

———, 2005b. “The ‘NEET’ Problem in Japan.” Social Science Japan 32(September):3-5.

——— & Mie Maganuma. 2006. NEET - Furita demo naku shitsugyōsha demo naku. Tokyo: Gentōsha.

Groos, Karl. 1898. The Play of Animals. New York: Appleton.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Haine, W. Scott. 1996. The World of the Paris Café: Sociability among the French Working Class, 1789-1914. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Hayashi, Sharon & McKnight, Anne. 2005. “Good-bye Kitty, Hello War: The Tactics of Spectacle and New Youth Movements in Urban Japan.” positions: east asia cultures critique 13(1):87-113.

Higuchi, Akihiko. 2005. “Kaiko to tenbō”, in Bungiten ni tatsu hikikomori. Osaka: Dōnatsutōkusha, pp. 8-11.

Huizinga, Johan. 1955. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston: The Beacon Press.

Ichino, Yoshiya. 2009. “Moshi ‘ikite itai’ to sura omoenaku nattara”, in Naoko Shimizu & Ryōta Sono, eds., Furītā rōso no seizon handobukku. Tokyo: Ōtsuki shoten, pp. 86-93.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. 2007. “Dead Bodies and Living Guns: The United Red Army and Its Deadly Pursuit of Revolution, 1971-1972.” Japanese Studies, 27(2):119-137.

Inui, Akio. 2005. “Why Freeters and NEET are Misunderstood: Recognizing the New Precarious Conditions of Japanese Youth.” Social Work and Society 3(2): 244-251.

Kaminaga, Kōichi. 1999. “Kokoro mondai to dameren”, in Dameren sengen!. Tokyo: Sakuhinsha, pp. 264-7.

Karatani, Kōjin. 2000. NAM Genri. Tokyo: Ōta shuppan.

———, 2003. Transcritique: On Kant and Marx. Cambridge, Mass. & London, England: The MIT Press.

———, 2005. “Kakumei to hanpuku: josetsu.” AT 0: 4-18.

———, 2009. Seiji o kataru, Tokyo: Tosho shimbun.

——— & Ryū Murakami. 2001. ”Jidai heisa no toppakō”, in NAM Seisei. Tokyo: Ōta shuppan, pp. 63-118.

——— & Hidemi Suga. 2005. “Seitai to shite no kakumei”, in Hidemi Suga, ed., Left Alone: Jizoku suru nyū refuto no “68 nen kakumei”. Tokyo: Akashi shoten, pp. 171-226.

Kosugi, Reiko. 2005a. “The Problems of Freeters and ‘NEETs’ under the Recovering Economy.” Social Science Japan 32 (September):6-7.

———, 2005b. “Furītā to wa dare ka.” Gendai shisō 33(1):60-73.

Kyūkyoku, Kyūtarō. 2006. “Sekai o shinkan sasenakatta mikkakan no yō ni.” VOL 1:167-170.

Mansbridge, Jane. 1994. “Using Power/Fighting Power.” Constellations 1(1):53 -73.

Marcuse, Herbert. 1998. Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. Oxon: Routledge.

Matumoto, Hajime. 2008a. Binbōnin daihanran—Ikinikui yo no naka to tanoshiku tatakau hōhō. Tokyo: Asupekuto.

———, 2008b. Binbônin no gyakushû: Tada de ikiru hôhô. Tokyo: Chikuma shobô.

McDonald, Kevin. 2002. “From Solidarity to Fluidarity: Social Movements beyond ‘Collective Identity’.” Social Movement Studies 1(2):109-128.

Melucci, Alberto. 1996. Challenging Codes: Collective action in the information age. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Mōri, Yoshitaka. 2005. “Culture = Politics: The Emergence of New Cultural Forms of Protest in the Age of Freeter.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6(1):17-29.

———, 2009. Sutorīto no shisō—Tenkanki to shite no 1990 nendai, Tokyo: NHK Bukkusu.

Nakajima, Akira. 2007. Chokugen kyokugen 2002-2006. Tonda: Magumagu.

Piven, Frances Fox & Cloward, Richard. 1977. Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. New York: Pantheon Books.

Polletta, Francesca. 1999. “‘Free Spaces’ in Collective Action.” Theory & Society 28: 1-38.

Rancière, Jacques. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Saitō, Tamaki. 2005. ‘Maketa’ kyō no shinjatachi: nīto hikikomori shakairon. Tokyo: Chūō kōron shinsha.

Sakurada, Kazuya. 2006. “Purekariāto kyōbō nōto.” Impaction 151:20-35.

Sawaji, Osamu. 2007. “Starting over.” The Japan Journal 1:6-10.

Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Schiller, Friedrich. 1967. On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Shiokura, Yutaka. 2002. Hikikomoru wakamonotachi. Tokyo: Asahi bunko.

Simmel, Georg. 1997. “The Sociology of Sociability”, in David Frisby & Mike Featherstone, eds., Simmel on Culture. London: SAGE, pp. 120-129.

Squires, Catherine R. 2002. “Rethinking the Black Public Sphere: An Alternative Vocabulary for Alternative Public Spheres.” Communication Theory 12(4): 446-168.

Tilly, Charles. 2000. “Spaces of Contention.” Mobilization: An International Journal 5(2): 135-159.

Toivonen, Tuukka & Miller, Aaron. 2010. “To Discipline or Accommodate? On the Rehabilitation of Japanese ‘Problem Youth’.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 22-6-10, May 31.

Toivonen, Tuukka & Norasakkunkit, Vinai & Uchida, Yūko. 2011. “Unable to Conform, Unwilling to Rebel? Youth, Culture, and Motivation in Globalizing Japan.” Frontiers in Psychology 2(207): 1-9.

Tsuji, Shin’ichi. 2001. Surō izu byūteifuru—Ososa to shite no bunka. Tokyo: Heibonsha.

Ueno, Toshiya & Gert Lovink. 2004. “Urban Techno Tribes and the Japanese Recession”, in Gert Lovink, ed., Uncanny Networks: Dialogues with the Virtual Intelligentsia. Cambridge. Mass. & London, England: The MIT Press, pp. 262-74.

Ueyama, Kazuya. 2000. “Hikikomori wa kekkyoku wa rōdōmondai da.” Nyūsutāto tsūshin 20 Nov, www.ns-kansai.org/nsk/ronso/ueyama-kazuki.htm (2005-06-13).

———, 2001. ’Hikikomori’ datta boku kara. Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Umano, Honesuke. 2008. “Binbō, zetsubō, osakimakkura—Nīto, hikikomori, menherā ni totte no rōdō seizon undō.” PACE 4:83-86.

Vaneigem, Raoul. 2001. The Revolution of Everyday Life. London: Rebel Press.

Williams, Jean Calterone. 2005. “The Politics of Homelessness: Shelter Now and Political Protest.” Political Research Quarterly 58(3): 497-509.

Yamazumi, Katsuhiro. 2001. “Kibō o tsumugu gakkō—nyūsukūru no kōsō ni tsuite”, in NAM seisei. Tokyo: Ōta shuppan, pp. 225-64.

Article copyright Carl Cassegård.